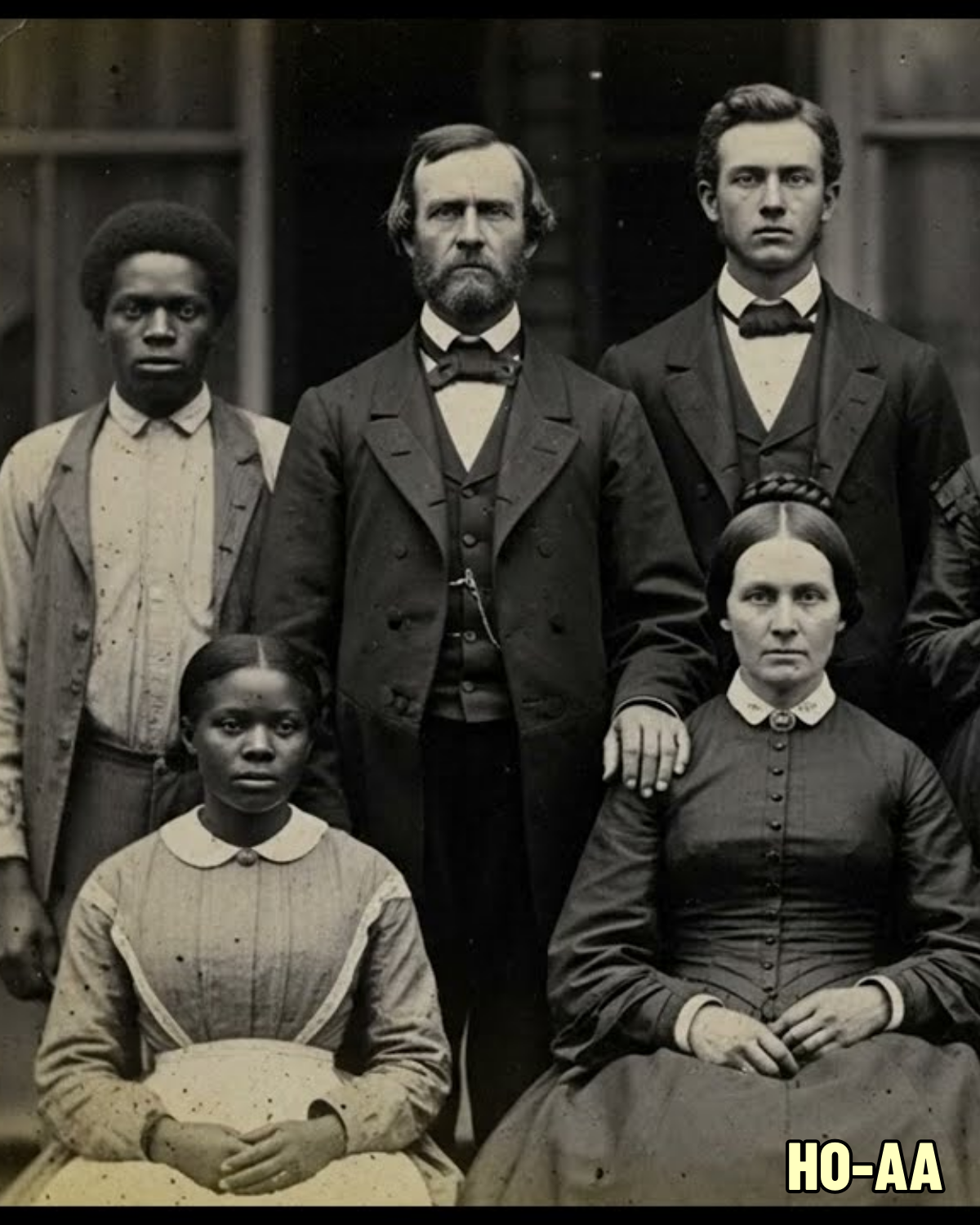

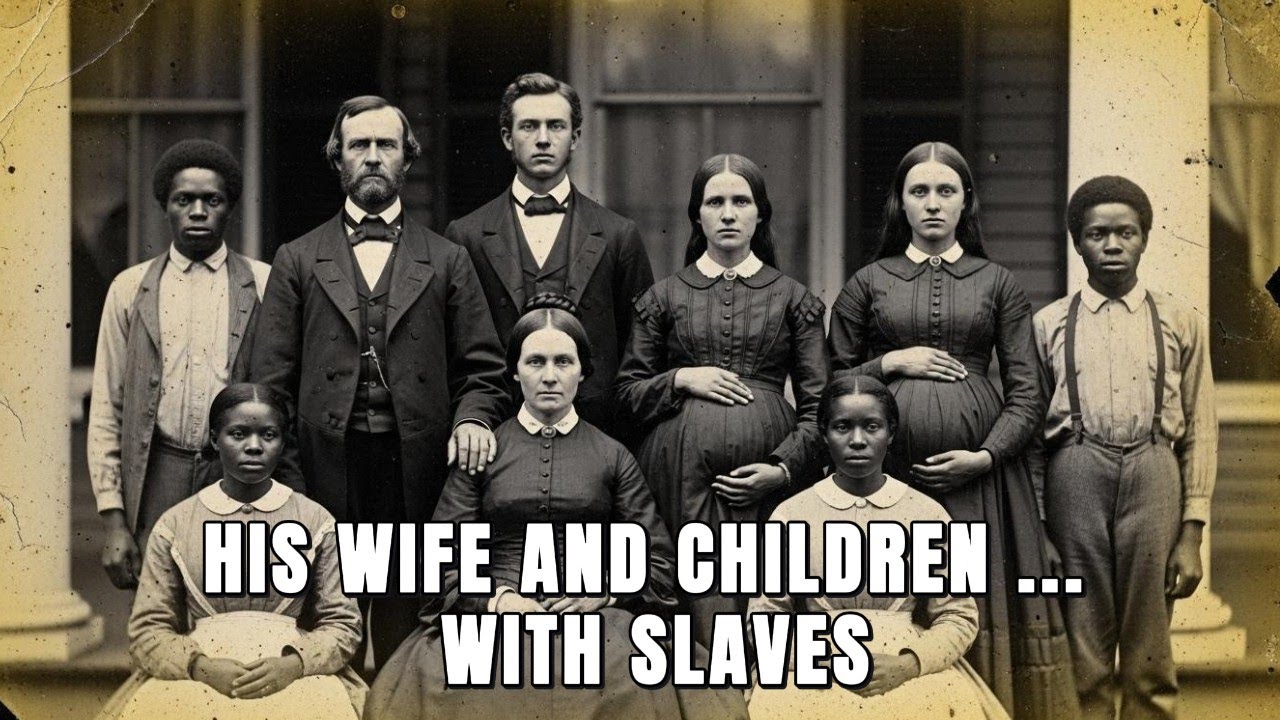

The Plantation Owner Who Bred Slaves with His Wife and Sons: Mississippi’s Scandal 1843 | HO!!!!

The Plantation Owner Who Bred Slaves with His Wife and Sons: Mississippi’s Scandal 1843 | HO!!!!

In the quiet archives of the Wilkinson County Courthouse in Mississippi lies one of the most disturbing records of the American South — a story so grotesque that officials once tried to erase it from history. Between 1835 and 1858, the Jessup family plantation operated under a system of cruelty and control that turned human life into arithmetic, intimacy into commerce, and family into an instrument of horror.

For twenty-three years, the Jessups of Woodville, Mississippi — a husband, a wife, and all five of their children — participated in what neighboring planters whispered about but dared never name aloud: a breeding operation. They forced enslaved men and women into reproductive servitude, often with themselves, to “grow their own stock” and ensure “generational wealth.” What makes this case uniquely chilling is not just its depravity, but its organization — a methodical, family-wide enterprise that blurred every boundary between faith, morality, and madness.

The Birth of a Monstrous Idea

The patriarch, Isaiah Jessup, arrived in Wilkinson County in 1829, a wealthy Virginian inheritor eager to expand into the booming cotton trade. By 1835, his plantation covered 1,200 acres of fertile delta soil and held forty-two enslaved people. His wife, Ruth Caendish Jessup, was the educated daughter of a South Carolina rice planter — a woman who knew the economics of slavery as intimately as her husband.

But Isaiah wanted more than cotton profits. He wanted control — control over life itself. Slave prices were rising. Infant mortality was high. And replacing lost laborers meant buying new bodies at immense cost. So one night in the winter of 1834, Isaiah proposed a solution to his wife that would turn their plantation into a private hell.

They would no longer buy enslaved workers. They would breed them.

To Isaiah, this was not sin — it was efficiency. He convinced Ruth that the children born of these forced unions would be stronger, healthier, and more valuable because they carried “Jessup blood.” By law, those children would still be enslaved, following the condition of their mothers. “It is an investment,” he wrote in his ledger. “An insurance of prosperity.”

Ruth hesitated. But then she agreed — on one condition: when their children came of age, they too would “do their part.”

The Education of Innocence

From the moment they could speak, the Jessup children were taught a language of power stripped of empathy. At the dinner table, Isaiah and Ruth discussed enslaved people as “resources,” “assets,” and “breeding stock.” They spoke of women not as mothers, but as “producers.”

Their tutor, a Kentucky man named Charles Whitfield, taught reading, writing, and scripture — but never challenged what the children learned at home. To young Thomas, Samuel, Margaret, Daniel, and Elizabeth, this was normal. By the time Thomas turned fourteen, he was inspecting fields and tallying the “value” of enslaved infants in his father’s ledgers.

When he turned seventeen, Isaiah summoned him to the study. A woman named Hannah, twenty years old and working in the kitchen, had been “chosen.” She would be brought to his room that night.

Thomas obeyed. He had been raised to believe it was duty.

Within months, Hannah was pregnant. Isaiah recorded the birth — a boy named Isaac — with satisfaction. “Healthy. Strong. Property of Jessup Plantation.”

A Family Business

By 1850, all five Jessup children were participants in the system. Thomas and his brothers Samuel and Daniel were ordered to impregnate enslaved women. Margaret and Elizabeth were forced to bear children by enslaved men “selected for desirable traits.”

Isaiah managed the program like a breeding stable. He tracked menstrual cycles, assigned partners, and rotated enslaved women to prevent “overuse.” Ruth oversaw pregnancies, ensuring the women were fed well enough to produce healthy offspring. Babies were taken from their mothers at age three and raised in separate quarters to prevent emotional bonds.

The ledgers — later discovered in 1962 — are cold, precise, and horrifying. Each line lists a name, date, birth outcome, and a notation of value. Children fathered directly by Isaiah himself were marked “J direct line.”

By 1855, the plantation population had grown from 42 to 68. Twenty-six were children under ten — all born from this program.

The Price of “Success”

Isaiah’s profits soared. He expanded his landholdings and built a new cotton gin. To the outside world, he was a model planter — pious, punctual, respected. He attended church every Sunday, served on the county agricultural board, and preached “Christian stewardship.”

No one questioned how his plantation grew so quickly. In the antebellum South, silence was custom. What a man did on his land was his own affair.

But behind the white columns and hymns, the family was fracturing. Samuel began drinking heavily, unable to endure what he was forced to do. Margaret slipped into depression after her fourth child was taken from her. Ruth hardened into cruelty, treating her daughter’s despair as weakness.

By 1857, cracks appeared in the machine Isaiah had built. Enslaved mothers whispered of rebellion. Their children, growing older, began to recognize their father’s faces in the white men’s features. Fear turned to rage.

The Spark of Defiance

The first act of open resistance came in 1859. Three women — Hannah, Rachel, and Julia — attempted to flee under cover of darkness. They made it six miles before being caught. Isaiah ordered them whipped publicly before every enslaved person on the plantation.

“We are fortunate,” he declared afterward, “to live under order, not chaos. They are property, and property must obey.”

That night, Samuel — drunk and shaking — confronted his father. “You’ve turned us into monsters,” he shouted. Isaiah struck him. Samuel left that night on horseback and never returned.

The same year, fire consumed the cotton gin. It was arson. No one confessed. Isaiah responded with random whippings, convinced the flames were a divine test. “The devil walks among them,” he wrote in his ledger. But those who lived in the quarters knew the truth — the fire had been set by seven enslaved men and women acting together.

It was the first time in twenty-four years that the enslaved people had struck back.

Collapse and Reckoning

The Civil War reached Mississippi in 1861. Thomas and Daniel enlisted with the Confederacy. Both died before the war’s end — Thomas at Shiloh, Daniel of disease in Virginia. Samuel drank himself to death in New Orleans years later.

Ruth died in 1864, consumed by guilt and grief. Her last surviving daughter, Elizabeth, remained at the plantation, too indoctrinated to see the evil around her. Isaiah, paralyzed by stroke, spent his final months in a wheelchair muttering scripture while the enslaved people quietly prepared to leave.

When Union troops arrived in 1865, the Jessup plantation was a ruin. The freed men and women gathered what little they had and walked away — some north, some west, all carrying scars that would last generations.

Isaiah Jessup died that October. His daughter sold the land two years later. The mansion collapsed into weeds before the century’s end.

The Discovery

A century later, in 1962, a locked trunk was found in a South Carolina attic. Inside were Isaiah’s ledgers — nearly 300 pages of neat handwriting documenting every birth, every sale, every “breeding pair.”

Historians were stunned. The records were more detailed than anything previously known about systematic slave breeding. They revealed not random cruelty, but a philosophy — a family who convinced themselves that organized sexual violence was simply good business.

The ledgers, along with oral histories from descendants of the enslaved, confirmed the unimaginable. One survivor, interviewed in the 1930s under the name Patience, said:

“Mr. Jessup ran that place like he was God. He decided who born, who live, who sold away. His own children did what he said. We wasn’t people to them. We was crops they was growing.”

The Legacy of Silence

Today, the Jessup plantation is gone — its fields divided, its name erased from maps. But DNA studies have revealed genetic links between white Jessup descendants and Black families across Mississippi, Louisiana, and Tennessee. Some have chosen to meet, seeking closure.

Others prefer to let the past rest.

Yet the story refuses to die, because it exposes something deeper than one family’s depravity. It reveals how an entire society could sanctify evil under the language of profit and piety — how ordinary men and women could turn birth into an industry and call it divine order.

Isaiah Jessup never saw himself as a villain. He died believing he was a righteous man, a good Christian, a careful steward of his property. His neighbors admired him. His church praised him. His ledger, however, tells the truth.

Page after page, line after line, in perfect handwriting: names, dates, prices, children.

It is not just the record of a plantation.

It is the anatomy of moral extinction.