The Bearded Slave Woman Who Could Father Children… Master Made Her Impregnate His Three Daughters | HO!!!! (zkf)

The Bearded Slave Woman Who Could Father Children… Master Made Her Impregnate His Three Daughters | HO!!!!

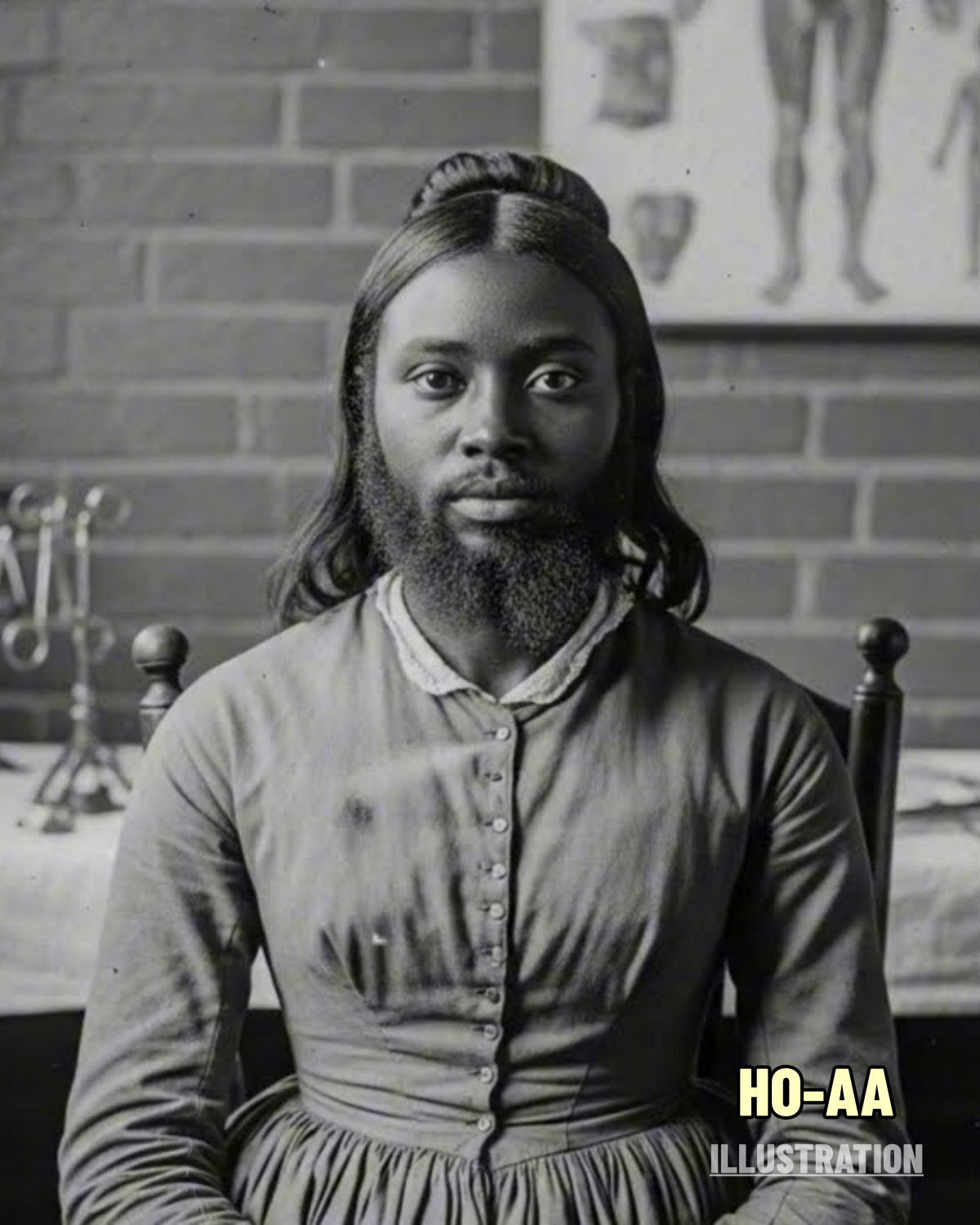

**The Bearded Slave Woman Who Could Father Children…

And the Master Who Forced Her to Impregnate His Three Daughters**

America’s Forgotten Horror in a Locked Virginia Room (1847–1863)

Between 1847 and 1863, inside a locked room on a quiet Virginia estate, something happened that three county clerks later refused to record in the public books. The few who whispered about it spoke of a bearded enslaved woman kept in isolation, three unmarried white sisters who mysteriously bore seven children, and a respected physician who called it “scientific research.” When Union soldiers finally opened the door to that room in April 1863, they found chains sunk deep into the floorboards, medical instruments whose purpose no doctor could explain, and a leather-bound journal written entirely in cipher.

Decades later, in 1906, the officer who deciphered that journal wrote in his private notes:

“I have seen battlefields, mass graves, and the starving bodies of prisoners.

But nothing disturbed me like understanding what transpired in that room.”

The case involved a woman the Covington family referred to only as the specimen—a Black woman whose rare intersex anatomy the master exploited, whose very existence challenged Victorian assumptions about gender, and whose captivity served purposes no court of that era had language to prosecute.

Seventeen miles from Charlottesville, buried in fragmentary records and testimonies collected decades later, lies a story so disturbing that two generations tried to erase it entirely. But history—even the parts we want to forget—has a way of resurfacing.

This is the investigation into one of America’s most horrifying hidden crimes.

I. Covington Manor: A House Built on Secrets

The spring of 1847 arrived cold and wet across the Virginia Piedmont. Morning fog clung to the valleys like spilled milk, and Covington Manor rose above it—an 800-acre estate of Georgian brick, white columns, and an outward respectability that concealed the rot inside.

Dr. Edmund Covington, 41 years old, balding, meticulous, and quietly unsettling, stood at his study window that March morning watching the fog burn away. To Albemarle County society, he was a brilliant physician, a widower, a man who educated his daughters far beyond what was typical for young women of their class. But beneath that veneer lived an ambition sharpened to a blade’s edge—a hunger for discovery that had no moral boundaries.

Sarah, 22, read Latin in the morning room, though her eyes kept drifting toward the road. Elizabeth, 20, practiced piano scales until they became a slow, hypnotic chant. Margaret, 17, worked alongside the household staff, her mind drifting somewhere far beyond chores.

Out in the slave quarters, thirty-seven enslaved people woke as they always did—not by sunlight, but by the rhythm of survival. They had learned the patterns of the house: when to be visible, when to vanish, when silence was safer than truth. Dr. Covington was not cruel in the conventional manner of slaveholding neighbors. But there was something colder in him—something colder than cruelty. He watched people the way a naturalist watches insects under glass.

Silas Fletcher, the senior hand, stood outside his cabin and stared toward the main house.

“Something’s changing,” he murmured. “Doctor’s been pacing, writing, traveling. Whatever’s coming… ain’t good for us.”

He was right.

II. The Arrival of the Bearded Woman

A covered wagon rattled into the yard that afternoon. Oddly, Dr. Covington himself came out to meet it—he never did that. He spoke in low tones with the driver, then reached up to help someone down.

Mya Dalton, working in the garden, caught the first glimpse.

At first she thought it was a young woman: slight frame, feminine dress, delicate movements.

Then the figure turned.

And Mya dropped her basket.

A beard.

A full, dark beard.

Not stubble, not stray hairs—a beard.

The newcomer was named Jordan Tinsdale, nineteen years old, sold from the Tinsdale Estate after its owner died. Listed as “female… unusual aspect… unsuitable for normal labor.” Bought for the low price of $340 because no one else wanted her.

To enslaved people, Jordan’s appearance was strange. To Dr. Covington, it was miraculous.

A living specimen of what he called “hermaphroditic development”—a term Victorian doctors used for intersex variations they neither understood nor respected.

Jordan was taken into the house through a side entrance no one had ever seen used. The door slammed behind her. It would not open again for sixteen years.

III. “The Research Opportunity of a Century”

Jordan’s new room was a converted storage chamber in the eastern wing. It had a bed, a washstand, a chair—and a lock on the outside.

Dr. Covington began examinations immediately, treating Jordan with the polite detachment of a scientist handling a rare specimen. He measured her skull, cataloged her voice pitch, sketched her face in meticulous detail. Jordan didn’t understand the medical terms, but she understood the gaze: clinical, fascinated, empty of humanity.

On the 21st day, the examination changed everything.

He discovered internal male reproductive anatomy alongside female characteristics.

And something else—

Something he believed could change medical history.

That evening, he summoned his daughters. He lectured for over an hour about heredity, reproduction, scientific progress. At first they listened with polite confusion.

Then Sarah understood what he was suggesting.

“Father… you are not proposing—”

“I propose nothing improper,” he said smoothly. “Only a controlled scientific study. For the betterment of mankind.”

They could agree… or they could leave with nothing. No protection. No prospects. No survival in a world where unmarried white women without family were socially doomed.

It wasn’t a choice.

It was coercion disguised as education.

IV. The First Procedure

Three weeks later, Sarah walked into the locked room like someone walking into her execution.

What happened behind that door was never recorded in detail. Even survivors could not describe it without breaking.

Two hours later, Sarah emerged hollow, shattered, her gaze fixed on something distant and unreachable. Her father wrote in his journal:

“Subject exhibited emotional agitation common in female nervous constitutions.”

Jordan remained locked inside, forced into the grotesque role the doctor had chosen for her—used like an instrument, like a biological tool, stripped of personhood.

By July, Sarah was pregnant.

In September, Elizabeth underwent the same procedure.

By November, both daughters were visibly expecting.

Dr. Covington invented imaginary husbands—three fictional Hartwell brothers who conveniently traveled for business. The community accepted the story without question.

Because in 1847 Virginia, men could create any fiction they wanted about women’s bodies.

And the world nodded along.

V. Seven Children, Seven Lies

Between 1848 and 1856, the sisters bore seven children.

Sarah had three.

Elizabeth had three.

Margaret, the youngest and most resistant, had one—after a desperate attempt to escape failed.

The children grew up amid careful lies. They were told their fathers were traveling merchants. They were taught to never ask questions.

But children always do.

Ruth, Sarah’s eldest, asked at eight years old:

“Why doesn’t Papa ever write to us?”

Sarah froze. “He will, darling. Soon.”

But Papa would never come home.

Because Papa didn’t exist.

Because their biological parent—the person whose cells created them—was locked in a windowless room, beard growing longer, body weakening, spirit dissolving.

Jordan watched the children grow only in glimpses—through cracks in doors, during procedures she could not stop, while surviving violations she had no language to describe.

VI. War Cracks the House of Silence

In 1862, a Confederate quartermaster accidentally opened the locked door.

He saw Jordan sitting on her bed.

A bearded enslaved woman.

A prisoner.

“Who are you?” he asked.

“Ask him,” Jordan whispered, nodding toward the doctor. “Ask him what… I’m for.”

The captain left disturbed. He told other officers. Rumors spread.

But the war marched on.

And Covington Manor kept its secrets—until Union cavalry arrived in April 1863.

Private Samuel Meredith forcibly opened the door. Jordan looked up, blinking at strangers for the first time in sixteen years.

She said only:

“Please… don’t let him close the door again.”

The soldiers searched the room. Then the house. Then the journals.

They confronted the daughters.

And the horror finally spilled out.

VII. Liberation Without Healing

The Union Army liberated Jordan and the enslaved people. They arrested Dr. Covington, uncertain what charges even applied.

Slavery had been legal when the crimes began.

White women could not legally accuse their fathers of rape.

Intersex bodies had no protections under law.

Medical ethics as we know them did not exist.

So they released him.

He returned home without punishment.

Sarah and Elizabeth broke under the injustice. Margaret, unable to endure another day under his roof, died by laudanum overdose three days later, leaving notes hidden around the house detailing the truth.

Sarah and Elizabeth fled with their children.

They never returned.

Their father never apologized.

Jordan entered a freedmen’s camp near Charlottesville. But freedom did not erase sixteen years of captivity.

“Free to do what?” she asked a Union private.

“I don’t know how to want anything.”

In 1863, she boarded a ship to Liberia. Missionary letters from 1865 mention a Black carpenter named Tinsdale—quiet, skilled, solitary.

It was likely her.

She lived, worked, and died on her own terms at last.

VIII. A Family Shattered for Generations

The children grew up believing their fathers were men who never returned. They carried the weight of secrets they couldn’t name. Many suffered depression, anxiety, identity confusion that echoed through generations.

Sarah and Elizabeth lived under assumed names, working in Baltimore and Washington as seamstresses until their deaths. They never rebuilt their lives fully. They never escaped the shadows of the locked room.

Dr. Edmund Covington died in 1865, mid-sentence in his journal, writing yet another justification for his “research.”

He died believing he had been right.

His grave sits in an overgrown lot behind a modern housing development, his name nearly erased by rain.

His victims were erased long before that.

IX. The Rediscovery

In 1908, the son of a physician who once corresponded with Dr. Covington found several of the hidden journals. He published a cautious academic paper—initials only, details removed—on coercion in antebellum medical “research.”

It barely caused a ripple.

Too disturbing.

Too complex.

Too true.

His paper mentioned “a bearded enslaved woman subjected to reproductive experimentation,” but avoided names and locations.

Local memory faded.

The estate was demolished.

A shopping strip replaced the entrance drive.

The cemetery sank into weeds.

But trauma does not vanish. It echoes.

And somewhere in America, the descendants of those seven children are alive—unaware of the truth buried in their family tree.

X. What This Story Teaches Us

The Covington case is not a ghost story.

It’s worse.

It is the story of how ordinary people, convinced of their own righteousness, can commit monstrous acts. How power—legal, medical, paternal—can warp morality. How individuals can be erased, their identities overwritten by the ambitions of others.

It is a story of:

a woman denied humanity because her body didn’t fit Victorian categories

three daughters trapped by a father who weaponized science

seven children born into lies

a community that sensed evil but lacked the power to stop it

a nation whose laws provided no protection for any of them

No justice was ever served.

No accountability recorded.

Only grief, scattered descendants, and the fragments of a truth that refuses to stay buried.

XI. The Final Question

When we uncover stories like this, we are forced to confront something uncomfortable:

How many more rooms were locked?

How many journals burned?

How many stories never reached the surface?

And how many descendants today feel a haunting weight in their families without knowing where it began?

History is not just what we record.

It is also what we hide.