This photo shows slave children playing — but experts saw what was on the ground | HO!

This photo shows slave children playing — but experts saw what was on the ground | HO!

When Dr. Michael Torres first opened the file, he expected another routine digitization—one more 19th-century photograph bound for the Library of Congress archives.

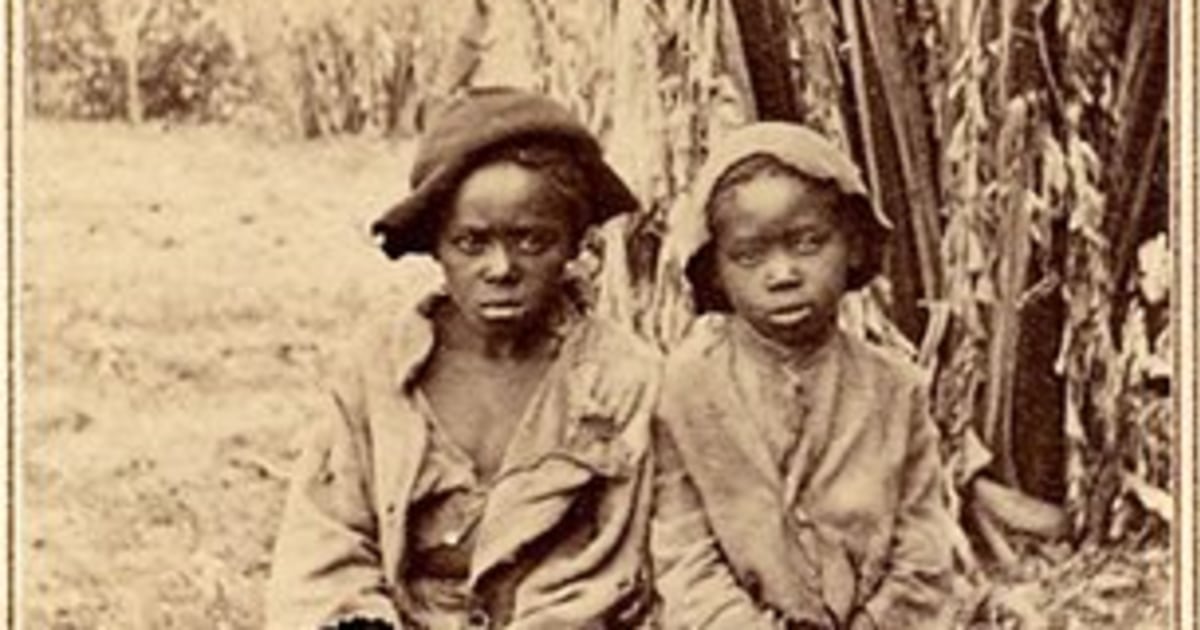

But the image on his monitor that morning in 2024—an 1854 daguerreotype labeled “Contented Negro Children at Play, Ashford Plantation, Georgia”—stopped him cold.

It showed five Black children, barefoot in a dirt yard, frozen mid-movement by the long exposure of early photography. Their smiles seemed hesitant but dutiful. The photo’s documentation called it “proof of the happy simplicity of our Negro children, who spend their days in carefree play.”

It was standard pro-slavery propaganda—the kind designed to soothe northern critics and defend the “peculiar institution.” But something about this picture unsettled Torres more than usual.

It wasn’t the faces. It was the ground.

Something Buried in Plain Sight

As part of routine preservation, Torres zoomed in on the digital scan—faces first, then clothing, then the dirt beneath them.

The magnification revealed faint shapes littered across the ground: small metal rings, broken chains, and wooden fragments.

At first, he assumed they were debris. Then, with trembling hands, he adjusted the contrast and shadows. The truth emerged.

Child-sized shackles.

Fragments of chains.

Carved wooden toys fashioned from punishment posts.

The children weren’t just playing.

They were playing with the tools of their own bondage.

Torres called Dr. Jennifer Washington, director of the American Memory Project. Within 20 minutes, she and historian Dr. Raymond Foster were at his workstation, staring at the screen in stunned silence.

“That’s a wrist shackle,” Foster whispered, pointing to a small iron loop near a child’s foot. “Designed for a six-year-old.”

Washington’s eyes moved to another section. “The girl in the center—she’s swinging a chain like a jump rope.”

Torres zoomed again. The carved wooden doll the smallest girl held wasn’t ordinary wood—it was dark, heavy, embedded with nails.

“That’s post wood,” Foster said grimly. “From a whipping frame. The stain is blood.”

The cheerful photograph that had circulated for 170 years as proof of slavery’s “benevolence” had, in truth, been a crime scene captured in plain sight.

The Records That Shouldn’t Exist

Foster traveled to the Georgia Historical Society to search the Ashford Plantation archives.

The archivist, Henry Crawford, led him into a climate-controlled room. “We have ledgers, invoices, punishment records,” he warned quietly. “They are… difficult reading.”

Within an hour, Foster found the entry that confirmed the unimaginable.

March 1852: Ordered from Charleston blacksmith, six juvenile restraints, $42.

The next ledger chilled him even more:

August 12, 1854 — Photographer Whitfield arrived. Children prepared for portrait. Restraints removed for photography session duration (2 hours). Play activity supervised in yard. Restraints reapplied following session.

That was the day of the photograph.

The children’s brief moment of “play” had been staged for the camera—two hours of pretend freedom ordered by a slaveholder seeking proof of happy servitude.

The children were named in the plantation’s birth registry:

Sarah (10), Thomas (8), Patience (7), Samuel (6), and Grace (5).

Tracing the Children

With genealogist Dr. Angela Morris, Foster began tracking the children’s names through post-war records. It took weeks of cross-referencing census rolls, marriage licenses, and Freedmen’s Bureau files.

Then, in an 1870 census from Burke County, they found her:

Sarah Ashford, age 26, living with husband Robert and three children.

She had survived.

Following her line forward, they reached Dr. Lorraine Hayes, a retired educator in Philadelphia—and Sarah’s great-great-granddaughter.

When Foster explained what he had found, there was silence on the phone.

“That little girl holding the chain,” Dr. Hayes said softly. “That’s my ancestor?”

“Yes,” Foster answered. “She was ten. Records say she’d been restrained earlier that same day.”

“My grandmother always said Sarah hated metal,” Hayes whispered. “Wouldn’t let the children play with tin soldiers or metal toys. She said metal was trouble. We thought she was superstitious. Now I understand.”

The Photographer’s Secret

While Foster traced descendants, Torres and Washington began digging into Charles Whitfield, the Savannah photographer who had taken the image.

His personal papers at the Savannah Historical Society revealed a startling find—a private journal spanning 1850–1865.

A July 1854 entry read:

“I am paid to create lies. They want smiling slaves, contented children, proof that bondage is humane. But what I see through my lens tells another story. I take their money because I must—but I know I am complicit in evil.”

Then, in August 1854, the very month of the Ashford session:

“Today I photographed the children. The overseer told them to play naturally, as if they remembered how. Around them lay chains, shackles, and toys carved from the posts of punishment. I framed the image to include these things. Perhaps one day someone will see what I saw. Perhaps truth will outlive the lie.”

Whitfield, it turned out, had embedded protest within propaganda—using his own commissioned work to smuggle truth into history.

Unearthing Proof

To verify the objects in the image, Washington enlisted Dr. Patricia Chen, a forensic archaeologist specializing in slavery-era artifacts.

After months of analysis and excavation at the Ashford Plantation site—now part of a wildlife preserve—Chen’s team unearthed:

Two child-sized iron shackles

Fragments of a chain identical to the photograph

Splintered wood from a whipping post

And a small wooden spinning top carved with the initials “S.A.”

“Sarah Ashford,” Foster whispered when he saw it.

The discovery transformed speculation into fact. The photograph wasn’t just propaganda. It was physical evidence of child enslavement, brutality, and resilience.

The Revelation

In February 2025, the Library of Congress held a press conference.

The same photograph that had once been used to defend slavery now filled a 20-foot projection screen.

At first glance: children at play.

Then, zoomed in—the truth: chains, shackles, blood-stained wood.

“For 170 years,” Dr. Washington said to the hushed audience, “this image was celebrated as evidence of humane slavery. But these children were not free. They were playing with the tools of their own restraint.”

She gestured toward the audience where Dr. Hayes stood, tears glinting under the lights.

“My great-great-grandmother Sarah,” Hayes said, voice trembling but strong, “was told to smile for this camera. She held a chain like a toy because that’s what they gave her. But she looked into that lens and made sure we would see. She bore witness the only way she could.”

The Re-Examination of History

The discovery triggered a nationwide project. Hundreds of 19th-century plantation photographs once dismissed as propaganda were digitally re-examined.

Over and over, researchers found hidden truths:

Scars on arms and legs of “happy” children.

Ankle restraints barely concealed under trousers.

Whipping posts just out of frame.

“These images were designed to lie,” Washington told a symposium. “But the camera couldn’t hide everything. The truth was always there—waiting for someone to look closely enough.”

From Horror to Understanding

Foster’s continued research showed that child restraint wasn’t exceptional. It was routine.

Plantations purchased juvenile shackles by the dozens. Children as young as four were bound for punishment or “discipline.”

Archaeologist Patricia Chen called it “a system of psychological control so complete that freedom became unimaginable.”

Yet among the artifacts, she also found hope—carved initials, decorative patterns, traces of imagination.

“They turned instruments of pain into toys,” she said. “That was resistance—small acts of reclaiming humanity.”

A Legacy Reclaimed

Educators soon grappled with how to teach this photograph responsibly.

Elementary students learned about resilience—the ability to create joy in impossible conditions.

Older students were taught to confront the image’s deception: how propaganda works, how to question what we’re shown.

Dr. Hayes often spoke at schools, standing beside projected images of her ancestor.

“This is Sarah,” she told them. “She was ten when she played with chains. But she survived. She had children. She built a life. And because of her, I stand here free.”

171 Years Later

On August 12, 2025—exactly 171 years after the photo was taken—a bronze memorial was unveiled at the former Ashford Plantation.

Five children, cast in bronze, stood in the same poses as the photograph. But this time, the chains and shackles were sculpted too—unmissable, undeniable.

Descendants of the enslaved filled the clearing beneath the Georgia oaks.

Dr. Washington spoke first:

“For generations, this image lied to the world. But these children refused to be erased. They held the truth in their hands—chains, toys, scars—and they waited for us to see it.”

Then Dr. Hayes approached the statue of Sarah, the child holding her chain like a jump rope, eyes lifted toward the camera that had once betrayed her.

“You did it,” she whispered. “We see you now.”