The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country | HO!!!! (sxp)

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country | HO!!!!

In the summer of 1839, Baltimore smelled of salt, tobacco, and rot—the perfume of an empire built on trade and denial. On a muggy Thursday morning, Dorothia Webb walked into Fells Point slave market with one silver dollar and a request that froze every trader in the room.

“Bring me the most repulsive man you have for sale.”

They thought she’d gone mad with grief. Her husband, Cornelius Webb, a wealthy shipping merchant, had died three days earlier—screaming, clawing at his throat, eyes fixed on something only he could see. The doctors found no poison, no marks. Just terror.

What followed would become one of the strangest, most quietly subversive stories in the history of American slavery: how a widow’s guilt, a scarred man’s wisdom, and a house haunted by invisible debts produced a transformation so profound that later generations would mistake it for myth.

I. The Merchant’s Curse

Cornelius Webb was the kind of man the early republic adored—refined, practical, untroubled by the moral arithmetic of commerce. His ships carried rice and cotton north, tobacco and rum south, and sometimes, when paperwork blurred conveniently, human beings in chains.

He liked to believe he’d never touched slavery directly. He just moved “cargo.”

But by 1839 the boundaries between profit and punishment had begun to close in. He stopped sleeping, stopped eating, muttered about “debts” and “eyes in the walls.” On the night he died, the servants heard him choking, his fingers gouging his own throat. When Dorothia burst in, he was already gray. His eyes—those glassy merchant’s eyes—were fixed on a dark corner of the room.

The city whispered: apoplexy, madness, guilt. Dorothia said nothing. She buried him, closed the drapes, and began reading.

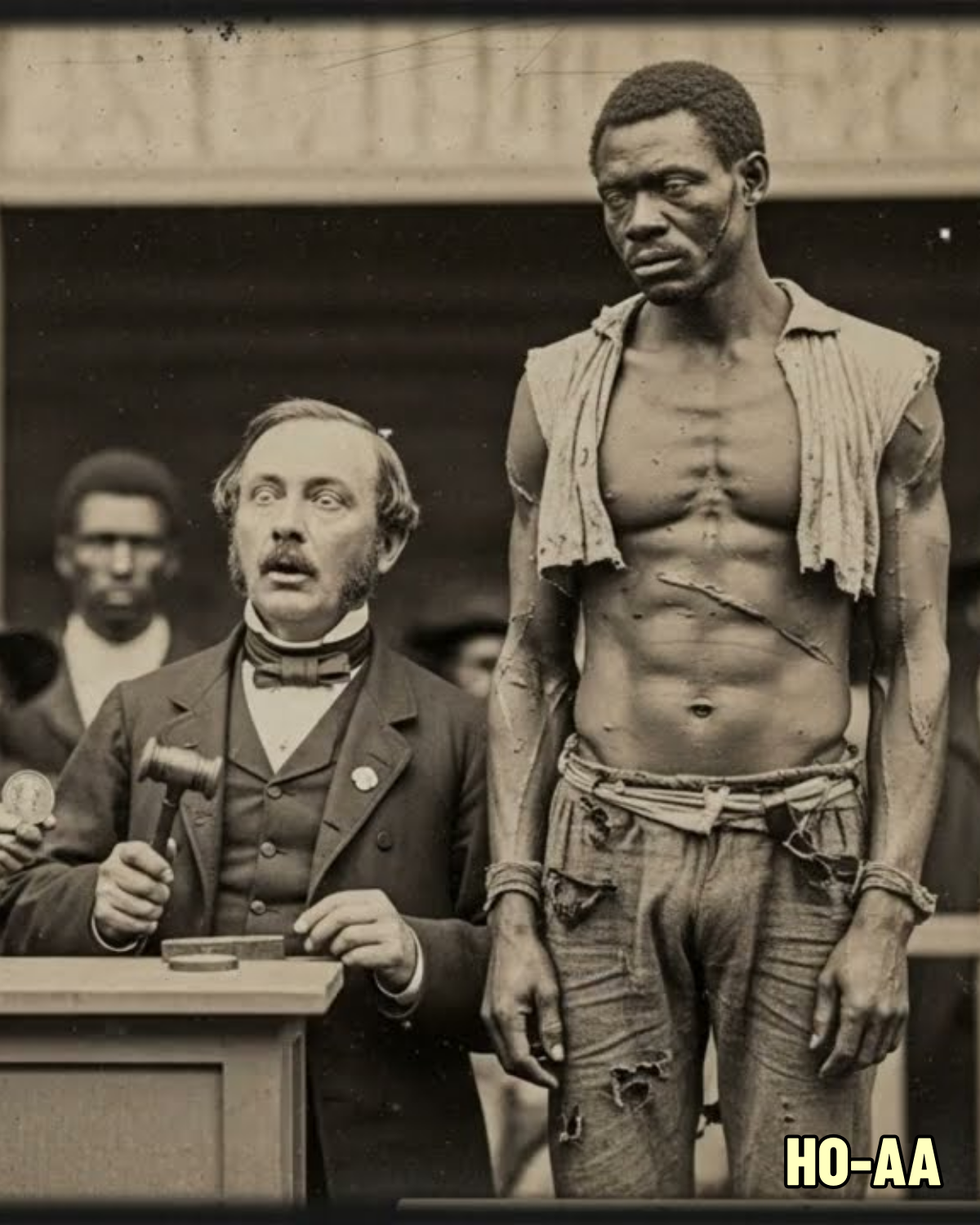

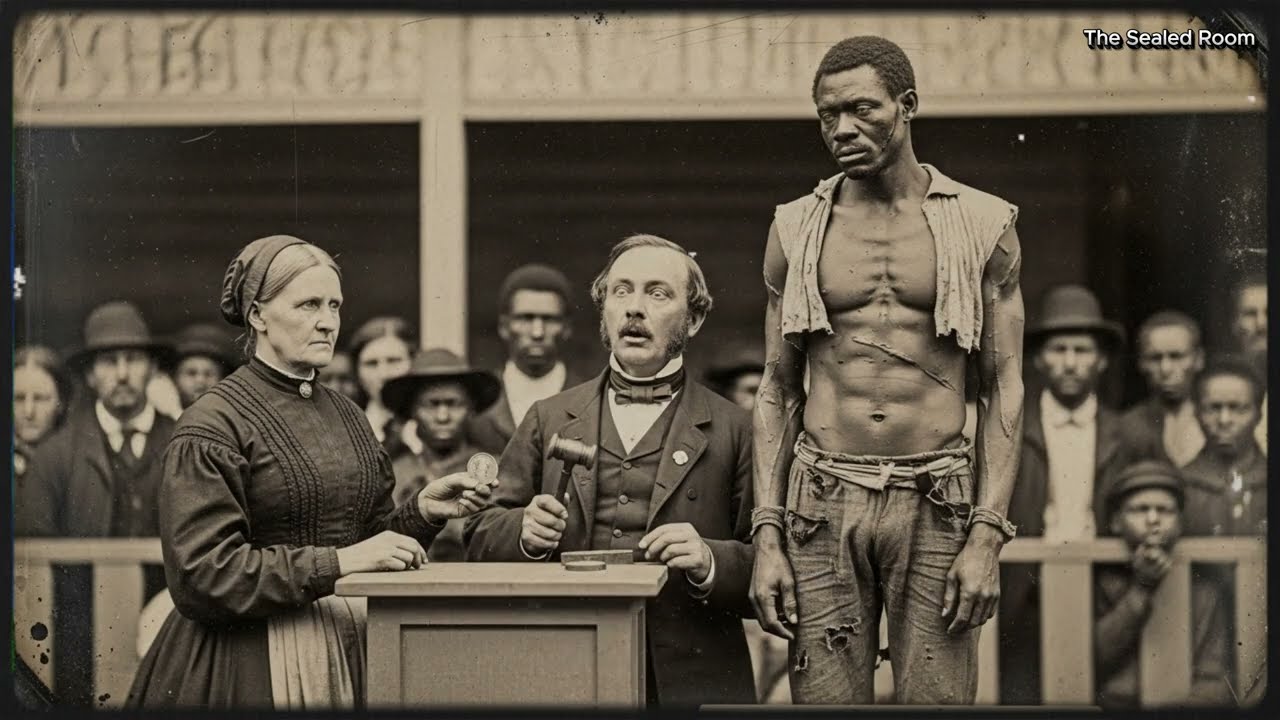

II. The Dollar Purchase

The widow who stepped into Fells Point market looked calm, almost serene. She wore mourning black and a veil that softened the sharp angles of her face. The traders smelled money and leaned forward.

“I’ll pay one dollar,” she said, “for the most repulsive man you have.”

They brought out Silas—six feet tall, burned or perhaps born disfigured, his left eye sealed under ridged flesh, his mouth pulled into a permanent half-grimace. Even seasoned traders turned away. He was worth nothing.

Dorothia handed over her dollar, signed the bill of sale, and walked him home through cobblestone streets lined with gawkers. The church bells tolled noon; to onlookers, it looked like a funeral procession for common sense.

III. The House on Thames Street

The Webb townhouse overlooked Baltimore Harbor—a fine red-brick symbol of mid-Atlantic respectability. Inside, grief had curdled into silence. The servants moved like ghosts.

Silas slept in a shed behind the carriage house. He spoke little, worked efficiently, and avoided mirrors. His presence unsettled everyone.

Dorothia spent her days in her husband’s study, reading his correspondence, tracing the ledgers that tied their fortune to southern plantations. The numbers felt obscene now—columns of profit annotated with initials that were once people.

Then came the noises.

Books fell by themselves. The smell of pipe tobacco—Cornelius’s brand—filled rooms where no one smoked. Papers rearranged overnight into perfect order. Something in the house was awake.

IV. The Inquiry

When medicine and prayer failed, Dorothia went to the Peabody Library and began reading about invisible causes—cases where people had died of fright, of guilt made flesh.

One letter, written by a physician in Jamaica, described deaths among slave traders who had “wronged others grievously.” He called it memory made manifest: guilt so deep it created its own executioner.

The pattern fit too perfectly. Cornelius’s ships. The men who never reached shore.

If the curse came from the drowned and the dead, she reasoned, perhaps only someone who had lived their suffering could understand it.

And so she bought a witness.

V. Conversations with the Scarred Man

Two weeks after Silas arrived, Dorothia summoned him to the study.

She asked three questions.

“What happened to your face?”

“Can you read and write?”

“Do you believe the dead can return?”

He told her the truth: that he’d been born marked, hidden by his mother, assigned to the filth work no one else would do; that he could read, secretly; and that yes, he believed suffering left fingerprints on the world.

Then she told him everything—her husband’s death, the moving shadows, the contract that valued human lives at fifteen percent mortality.

Silas listened and said, “Then the ones who died have found him. And they’ve found you too.”

VI. The Ritual of Reckoning

They began at midnight.

The servants were sent away. The study was cleared, chalked with symbols Silas remembered from the plantations—gateways between worlds.

He told her to speak.

She confessed aloud what the ledgers hid: I speak to those who died in the ships my husband profited from… I acknowledge that you were murdered in the name of comfort and respectability.

The air turned cold. The candles guttered. Figures began to form—translucent, watchful, human.

“I have freed ten people in your names,” she said, placing manumission papers on the desk. “It is not enough. But it is what I can offer.”

One woman’s shade stepped forward, wrists scarred by chains.

“We accept your offering,” she said. “Not because it is enough, but because it is honest. The debt remains. You will carry it.”

And then they were gone.

Silas told her, “You will live. But you will pay, every day you have left.”

VII. Freedom for $1

She kept her word. He kept his.

The next morning, she handed him manumission papers, $500, and a letter to a Quaker printer in Philadelphia.

“You are free, Silas,” she said.

He bowed, not as servant to mistress but as equal to equal. “And you, ma’am,” he said, “are free of the worst kind of blindness.”

Then he walked down Thames Street into the mist and did not look back.

VIII. The Years of Atonement

Baltimore society watched in horror as Dorothia Webb dismantled her privilege piece by piece. She sold the shipping business, freed dozens of people, turned her home into a boardinghouse for the formerly enslaved.

They called her unstable, unfeminine, damned. She ignored them.

Silas, meanwhile, became something else entirely. In Philadelphia he learned the power of words. The Quakers discovered his literacy, and soon his essays appeared in abolitionist pamphlets—signed only with an initial. His scarred face became an emblem, sketched on posters beneath the caption A Testament to the System’s Cruelty.

By 1842, people spoke his name with reverence. The ugliest man ever sold had become a prophet of freedom.

IX. The Transformation

Silas’s presence seemed to strip away deceit. Slave-catchers found themselves confessing lies. Politicians stammered under his stare.

Some swore he could see into their hearts. Others said his scars glowed in candlelight, though that may have been imagination—the way guilt amplifies the supernatural.

He freed twelve more people with his own earnings. He refused every offer of marriage. “The work isn’t finished,” he said.

His correspondence with Dorothia continued, letters full of exhaustion and resolve. Neither mentioned the ritual again, but every word carried its echo.

X. The Final Meeting

In 1851, Silas returned to Baltimore to speak at a Methodist church newly turned abolitionist. Dorothia, gray-haired and thin, sat in the back.

He spoke of contracts, mortality rates, and the arithmetic of evil. He never named her, but when his eyes met hers, everyone felt something pass between them—recognition of a night when truth itself had taken shape in candlelight.

Afterward, they spoke briefly.

“Do you believe it was real?” she asked.

He answered, “Real enough to change us. That’s all that matters.”

She died later that year.

XI. The Most Desired Man in the Country

By the 1850s, Silas was an elder in the abolitionist movement. Frederick Douglass cited him in speeches. Garrison printed his essays. His scarred visage appeared in daguerreotypes distributed across the North.

He was, paradoxically, beautiful—not by symmetry but by meaning. People saw in his disfigurement what they wanted to believe about themselves: that suffering could be transformed into purpose.

When emancipation came in 1863, he wept for the living and the dead. “Freedom,” he said, “is only the first payment.”

He died ten years later. At his funeral, Douglass said:

“We looked at Silas and saw ugliness. Then courage. Then wisdom. Then beauty earned through suffering. He taught us that how we see depends on what we are willing to recognize.”

XII. Echoes in the Archives

Historians lost the trail. The manumission record remains—$1, Baltimore, 1839—but the rest scattered across archives and rumor.

What survives is pattern: a widow who sought atonement, a man who turned disfigurement into testimony, a haunting that demanded acknowledgment instead of exorcism.

Some say the Webb house still breathes faint tobacco smoke at midnight. Tourists at Fells Point sometimes feel a weight in the air, a presence that watches but does not accuse.

Maybe imagination. Maybe memory made manifest.

XIII. The Debt That Remains

The ritual in that Baltimore study did not end anything. It began a negotiation that continues still—the question of what’s owed for comfort built on cruelty, of how acknowledgment can coexist with survival.

Silas understood: beauty, value, desire—none are inherent. They’re assigned, and therefore can be reassigned.

He proved that the ugliest man at auction could become the most desired not because his face changed, but because people finally learned to see differently.

XIV. Epilogue

If you walk past the old slave-market site today, there’s a small plaque. It doesn’t mention Dorothia Webb or Silas. It doesn’t mention the night of the ritual or the way a dollar purchase rewrote two lives.

But sometimes, in the hush between harbor winds, visitors swear they smell tobacco and rosewater, hear the faint scratch of a quill, feel the room tilt toward recognition.

Maybe it’s history breathing.

Maybe it’s the echo of a debt still seeking payment.

Either way, it asks the same question that haunted Dorothia and redeemed Silas:

Are you willing to sit in darkness and see what appears when the lies are stripped away?