The Plantation Owner Bred His Blind Daughter with 11 Slaves — What Was Born Destroyed Carolina | HO!!!!

The Plantation Owner Bred His Blind Daughter with 11 Slaves — What Was Born Destroyed Carolina | HO!!!!

It began with a fire.

On an October night in 1923, the Dupin County Courthouse in Kenansville, North Carolina, went up in flames. By morning, only fragments of charred papers remained — land deeds, birth certificates, court transcripts — blackened curls of history too stubborn to die completely.

Among the debris, a clerk found two birth certificates for the same person. Both bore the year 1827. Both claimed to document the birth of a woman named Elizabeth Vance. One listed her parents as Nathaniel and Margaret Vance, of Hollowest Plantation. The other, dated the same day, listed her mother as “Sarah — enslaved woman, deceased,” and her father as “unknown.”

The discovery made no sense. But it cracked open something the county had buried for almost a century.

What began as a curiosity in a historian’s notebook would lead to one of the most horrifying revelations in Carolina’s past — a story of greed, desperation, and the grotesque logic of slavery. A story in which a plantation owner, drowning in debt, looked at his blind daughter and saw not tragedy, but opportunity.

I. The Decline of Hollowest

Somewhere between the tobacco fields of eastern Carolina and the Cape Fear River, Hollowest Plantation stood like a dying monument to Southern ambition.

In its prime, it had been a jewel — 470 acres of fertile land, three stories of cypress and brick, and a family name that once carried weight in Wilmington and Raleigh. But by 1839, Hollowest was collapsing under the weight of its own history. The soil had soured from overuse. The crops failed. The neighbors whispered.

At the center of this decay was Nathaniel Vance, a man born into wealth and educated into ruin. At forty-seven, he still looked like prosperity — tall, broad-shouldered, his dark hair slicked back with pomade — but his fine coats were years out of date, and his boots were polished by the same man he’d considered selling last winter.

He’d inherited Hollowest a decade earlier and spent the years since clawing to preserve its image. Each year, fewer workers remained. Once, the plantation had 87 enslaved people. By 1839, only 32. The rest had been sold — families torn apart and auctioned like furniture to cover his debts.

The merchant bank in Wilmington held the deed. Interest mounted. Creditors circled. And behind the locked doors of the great house, the Vance family was unraveling.

II. The Blind Daughter

Nathaniel’s first wife, Catherine, had died in childbirth in 1829, leaving behind two small graves and one surviving child. His second wife, Margaret — younger, prettier, and richer — arrived from Charleston with a dowry large enough to keep the estate afloat. She gave birth to a daughter, Elizabeth, during an ice storm in 1827.

By the second day, the midwife, a free woman of color named Ruth Carver, realized something was wrong. The baby’s eyes didn’t follow light. Her pupils didn’t contract. When Ruth waved her hand before the infant’s face, there was no reaction. The child was blind.

Ruth told Nathaniel carefully, knowing how men like him responded to imperfection. He paid her triple her usual fee, forced her to sign a paper swearing the baby was “healthy and normal,” and warned her never to speak of it again.

Margaret lasted another eighteen months. One April evening, she took forty drops of laudanum and never woke up.

By then, Nathaniel’s heart had hardened. He raised Elizabeth alone, keeping her confined to the second floor of the house — a pale figure in shuttered rooms, taught to navigate by touch. Her world was made of texture and echo: the grain of the walls, the creak of the stair, the sound of Ada’s voice — the house slave who cared for her from infancy.

She learned to count steps, to distinguish rooms by smell and sound. But her father saw her blindness not as fragility, but as failure — a reminder of his declining fortune. In a world that measured women by beauty and marriageability, Elizabeth was worthless.

And Nathaniel was running out of things to sell.

III. A Monstrous Idea

In the winter of 1839, while studying his late father’s legal papers, Nathaniel came across an obscure North Carolina statute from 1791 — a case involving the classification of children born to enslaved mothers. It described how, under certain circumstances, a child’s status could be determined not by morality, but by documentation.

As he read, a terrible calculation formed in his mind.

If he could falsify his daughter’s birth records — if he could create a paper trail claiming she was born to an enslaved woman — then any child she bore would legally be property.

And property could be sold.

To make it work, he needed accomplices.

He wrote three letters.

One went to Dr. Ephraim Stokes, the local physician and coroner — a man deep in debt. Another went to Magistrate Calvin Pritchard, who controlled the county’s legal records — a gambler drowning in loans. The third went to Thomas Harrington, a slave broker in Wilmington who specialized in “unique acquisitions.”

Each man understood the coded language in Nathaniel’s letters. Each saw the same thing: profit.

By spring, they had agreed. The conspiracy had begun.

IV. Preparing the Victims

Over the next year, Hollowest changed in subtle ways. Eleven men — young, strong, light-skinned — were moved from the fields into the main house. They were told they were being trained as house servants. They were fed better, given clean clothes, lighter work. But the real reason was something none of them could imagine.

Their names were Jacob, Daniel, Isaac, and eight others whose names history barely preserved. Nathaniel had selected them as if breeding livestock — choosing for height, symmetry, complexion. Each was trapped between obedience and terror.

Elizabeth, now sixteen, was unaware of any of this. Her world remained the dimly lit rooms upstairs, where Ada read to her in secret and carved raised letters into wood blocks so she could learn by touch.

But changes came. Nathaniel began insisting she dine downstairs once a week. He spoke of “family duty” and “the legacy of Hollowest.” He told her she was part of something important — something that would save their home.

She didn’t understand. How could she?

V. The Machinery of Evil

Dr. Stokes visited often, examining Elizabeth under the guise of ensuring her health. His notes were written in careful, detached script — “patient in good condition, suitable for future fertility.”

Magistrate Pritchard spent his nights drafting papers: two birth certificates for Elizabeth, one true and one false; a fictitious lineage claiming her mother was an enslaved woman named Sarah; a web of signatures and seals that made lies look like law.

Thomas Harrington, the broker, wrote discreet letters to clients in Charleston, Baton Rouge, and Richmond. He described an “acquisition of exceptional quality” — a child soon to be born “of rare lineage and complexion.”

No one asked how. No one wanted to know.

By 1843, every piece was in place.

And by the winter of 1845, Elizabeth was eighteen — “of age,” by the standards of her time.

That spring, Dr. Stokes certified her “fit for maternity.” Nathaniel nodded. The clock began.

VI. The Year of Horror

The months that followed defy language.

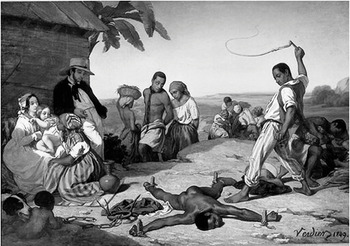

What Nathaniel Vance did in 1845 and 1846 was not a single act of violence, but a system — an organized, documented crime masquerading as legality.

The eleven men were brought to the house, one after another, under threat of punishment or sale. The enslaved woman Ada, forced to care for Elizabeth through it all, could do nothing but witness.

By July, Dr. Stokes confirmed that Elizabeth was pregnant.

The doctor recorded every stage clinically: “progressing normally, no complications.” Magistrate Pritchard finalized the papers that would classify the unborn child as property — “Mother: Sarah (deceased). Father: unknown.”

Elizabeth understood nothing. She felt the life moving inside her and asked Ada why. Ada had no answer she could give.

VII. Birth and Sale

On March 4, 1846, after twenty hours of labor, Elizabeth gave birth to a boy. He was healthy, strong, with skin the color of light bronze and eyes like deep water.

Elizabeth asked to hold him. Her father refused.

Dr. Stokes took the newborn downstairs to the study, where Magistrate Pritchard sat waiting beside the ink and seals. They filled in the certificate. The child was listed as the property of Nathaniel Vance.

The infant was named Thomas.

Nathaniel wrote to Thomas Harrington. The bidding began.

By April, the price had reached $4,700 in gold — an enormous sum. The buyer was Charles Rutledge, a sugar baron from Baton Rouge known for his collection of “exotic acquisitions.”

He arrived at Hollowest in a private coach. Nathaniel showed him the child as though displaying an antique. Rutledge examined the infant with clinical interest — the skin tone, the symmetry, the calm temperament. “He’ll do nicely,” he said.

The deal was completed within hours.

Upstairs, Elizabeth heard the carriage wheels rolling away and the sound of her child crying. Ada told her softly, “They’ve taken the baby.”

Elizabeth whispered, “Where?”

Ada’s answer broke her: “You’ll never see him again.”

VIII. Silence and Madness

Nathaniel paid off the bank in Wilmington the next morning. The foreclosure was canceled. Hollowest was saved.

But the price of his salvation was a silence that began to unravel the house from within.

By winter, one of the enslaved men — Isaac — tried to end his life. He was stopped, punished, and sold to Virginia. Others were scattered to different plantations. Ada grew hollow-eyed, mechanical, her faith in the world shattered.

Elizabeth stopped eating. She spoke less each day.

In March 1847, she began to scream without warning. Dr. Stokes diagnosed “nervous hysteria” and prescribed laudanum. For weeks, she drifted in and out of consciousness, trapped in fog.

Her father called it an inconvenience.

IX. The Minister Who Knew

One man refused to let it rest: Reverend Thomas Gaines, the local minister Nathaniel had once insulted in church. He arrived unannounced that June while Nathaniel was away. Ada, exhausted and desperate, broke her silence. She let him in.

Upstairs, the Reverend found Elizabeth pale and trembling, her sightless eyes open. When he spoke to her gently, she told him fragments of the truth — about the men, the child, the confinement.

The story came out in broken pieces, but it was enough.

When Nathaniel returned and discovered the visit, he confronted Gaines with icy calm. “My daughter is ill,” he said. “She suffers delusions. Ask the doctor. Ask the magistrate.”

Gaines left the house shaken. He began asking questions — quietly, cautiously — in town. But no one helped him. Pritchard was in Nathaniel’s pocket. Stokes was complicit. Harrington had vanished south.

Without evidence, the minister was powerless. His notes went into a journal, locked in a church drawer where they would remain for nearly a century.

X. The Aftermath

Years passed.

By 1850, the plantation was stable again. Nathaniel presented himself as a respectable widower caring for an invalid daughter. He even attended church on occasion, sitting in the same pews as men who’d helped him falsify the documents.

Elizabeth lived in near-total isolation, confined to her room, her mind eroded by grief and opium. Ada stayed with her until old age, caring for her in silence.

The eleven men were all gone — sold, relocated, or dead.

And the child, Thomas, grew up in Louisiana, a slave in a world that believed him born to bondage. His true mother’s name never reached his ears.

When the Civil War came, the house still stood. Nathaniel lived long enough to see emancipation destroy the world he had built on paper and deceit. He died in 1871 at age seventy-nine — found slumped over his desk with an open ledger and an empty whiskey bottle.

He died rich and unpunished.

XI. Discovery

The truth might have vanished entirely if not for the 1923 courthouse fire.

In the ruins, historian Harold Jensen found the twin birth certificates. The contradiction led him down a rabbit hole: property ledgers, medical logs, letters. He uncovered a bill of sale for an infant named Thomas, sold in 1846 by Nathaniel Vance to Charles Rutledge of Louisiana — for $4,700 in gold.

He found references in Dr. Stokes’s journals to “unusual cases” and notes in Pritchard’s ledgers written in different inks, suggesting retroactive edits.

In 1931, Jensen’s research was validated when church archivists discovered Reverend Gaines’s diary. The entries matched Jensen’s findings almost exactly.

Then, in 1947, a new piece emerged — Ada’s letters, found by her descendants. They were unsent, brittle with age, written in shaky but legible script.

“I witnessed evil that I could not stop,” one letter read. “He made her bear a child and sold that child for gold. I prayed for God to strike the house down, but He did not. Perhaps the fire will be His answer.”

XII. The Truth That Refused to Die

By the 1950s, Hollowest Plantation had fallen to ruin. The main house collapsed in a storm, leaving only its brick foundation and a half-buried cellar. The land became timber forest — quiet, unmarked, unremembered.

But the story had already escaped its walls.

Historians pieced together the timeline:

Nathaniel Vance, landowner in debt, orchestrates a conspiracy to breed his blind daughter with enslaved men.

Dr. Stokes falsifies medical records.

Magistrate Pritchard forges birth certificates.

Broker Harrington arranges a sale.

The child is sold to Louisiana and disappears.

Each man profits. Each man dies without punishment.

And the victims — Elizabeth, Ada, the eleven men, and the child who never knew his name — vanish into the gaps between law and morality.

To this day, no one knows what became of Thomas. He might have died in infancy, or escaped during the war, or lived out his years believing he was born to chains.

What is certain is that his birth — and the system that made it possible — left a stain so deep that even fire couldn’t erase it.

XIII. Reflection

The story of Hollowest Plantation isn’t simply a tale of one man’s depravity. It’s a mirror held to an entire society that made such depravity possible — and profitable.

Nathaniel’s crime was not that he broke the law. His genius, if one dares call it that, was that he used the law exactly as written. He found the seams in a system designed to turn people into assets and used it against his own blood.

He was not an aberration. He was its purest expression.

When historians argue that slavery was “complicated,” that moral judgment must consider its context, stories like Hollowest shred those excuses. The horror here was not hidden in the shadows — it was signed, sealed, and notarized.

XIV. The Land Remembers

Drive through Dupin County today and you’ll pass soybean fields, pine trees, a stretch of dirt road that turns to dust in summer. There’s no marker for Hollowest. No plaque. Just a rise in the earth where the house once stood and, if you listen carefully at dusk, the faint sound of wind through the trees — like breathing.

Locals still talk about it, quietly. Some say the soil never grew right afterward. Others claim you can hear a woman singing at night near the ruins, her voice thin and echoing, as if calling for a child that never came back.

But history, when it speaks, does so not through ghosts, but through paper — burned, waterlogged, half-saved by accident.

And those papers tell a story that no one wanted to remember, but that refuses to be forgotten.

Epilogue: The Question That Remains

In the end, the documents — the letters, the certificates, the diary, the fire — all circle back to one question: How many more Hollowests existed?

How many conspiracies died unrecorded because the people who suffered them were silenced, sold, or buried?

The truth uncovered in 1923 didn’t destroy just one family’s legacy. It tore open the myth of Carolina gentility — the illusion of noble planters and moral order. It revealed that behind the white columns and magnolia trees, there had always been a ledger balancing sin and profit.

Nathaniel Vance thought he had saved his plantation. In the long run, he destroyed it — and everything his name ever meant.

What was born in that house did not just damn a family.

It condemned a system.

And in doing so, it revealed what every society built on silence must eventually face — that no matter how carefully the truth is buried, fire has a way of finding it.