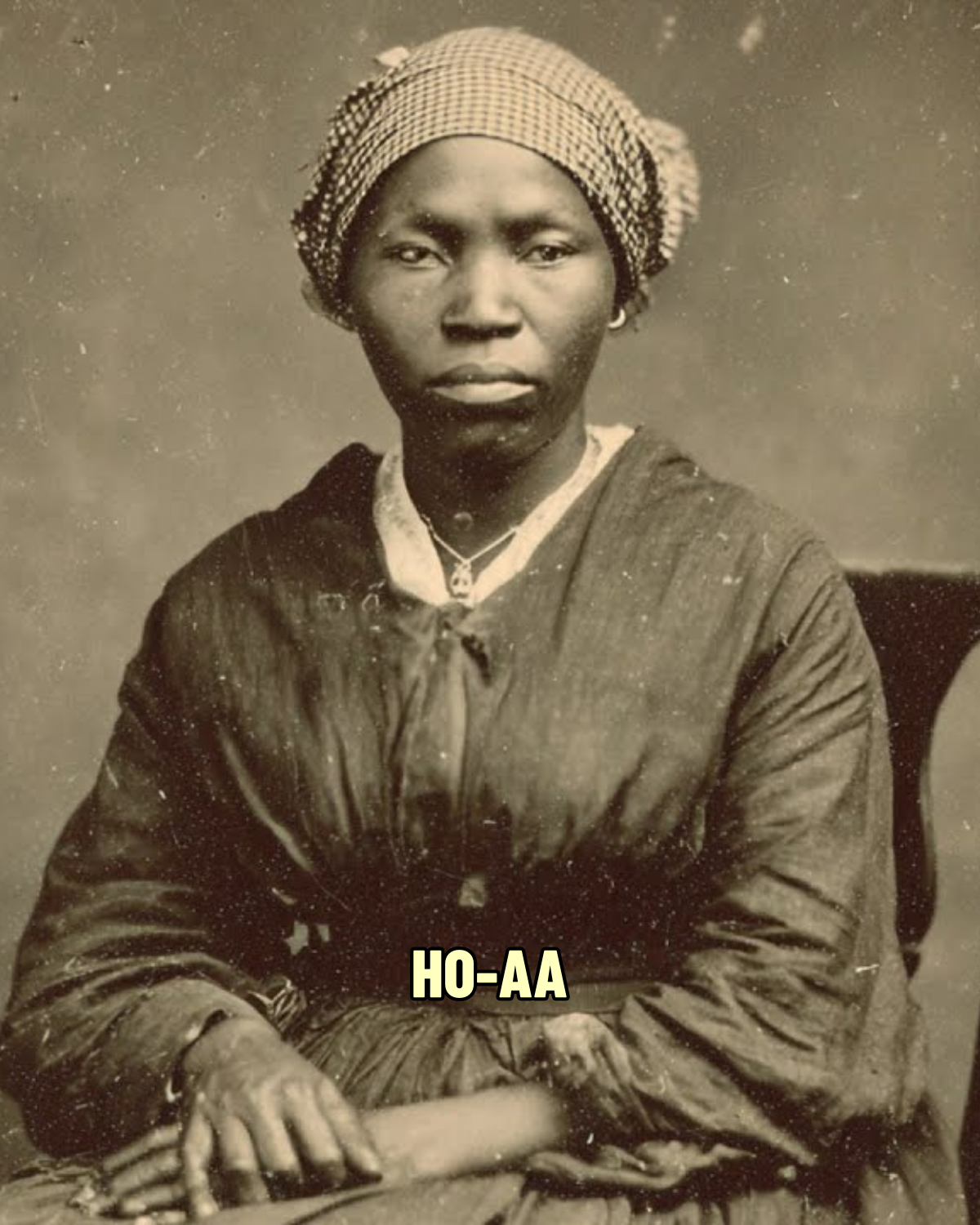

The Mississippi Sisters Who Married Their Slaves: The Hidden Pact of 1848 | HO!!!!

The Mississippi Sisters Who Married Their Slaves: The Hidden Pact of 1848 | HO!!!!

PART I — THE TRUNK BENEATH THE ALTAR

1. The Discovery

In the summer of 1959, a demolition crew contracted to clear the last standing structure of the old Belelfford Hall estate in Adams County, Mississippi, stumbled onto a discovery that would rupture the county’s own carefully tended amnesia.

The plan was simple: tear down the half-collapsed chapel before it slid completely into the gully behind it. The men approached without reverence. They had been told the building had been empty for a century, good only for snakes and memories.

But as they tore up the rotten floorboards around the altar, their crowbars struck iron.

Beneath the boards lay a trunk, blackened, bound with rust-swollen metal straps, and inexplicably—impossibly—still locked.

The workers assumed it held communion vessels or family heirlooms. What they pried open instead was the beginning of a story so grotesque, so inverted from the county’s myth of itself, that local officials quietly ordered the artifacts impounded before historians could touch them.

The trunk contained:

A brittle, water-damaged diary

Two parchment marriage certificates dated September 1848

A small iron crucifix with four names scratched into its arms

The ink on the certificates had browned and flaked.

Except it wasn’t ink.

Laboratory testing later confirmed:

the signatures were written in human blood.

It was the first clue that the story of the Winthrop family—once praised as Christian philanthropists and pillars of Adams County—was far darker than the county had ever dared admit.

It was the opening crack in a century-long cover-up.

2. The Family Behind the Ruin

Belelfford Hall had been one of the most imposing plantation estates along the Mississippi River in the mid-19th century. The Winthrops were known publicly as moralists—church-builders, scripture-quoters, guests of honor at every civic event. Their patriarch, Judge Henry Winthrop, had a reputation for stern legality but fair judgment.

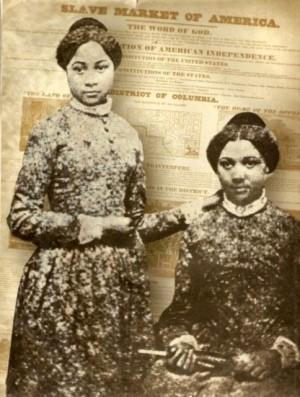

When he died in 1848, his two daughters—Claraara and Margaret Winthrop—became the last female inheritors of a dynasty that had survived cotton panics, river floods, and disease.

Within a year, their story had collapsed into rumor:

Two sisters driven mad by fever.

A tyrannical brother who returned from Virginia to “care” for them.

A mysterious death no one dared question.

A plantation that slid into quiet ruin.

Two reclusive women who died together in the family chapel during the Civil War.

For a century, local folklore reduced them to caricatures:

the Mad Sisters of Belelfford Hall.

But the diary in the trunk revealed a narrative so different, so raw and human—and so incriminating—that historians immediately recognized what officials had probably understood the moment they saw it:

This was never madness.

It was a suppressed rebellion.

A love story punished into silence.

A crime covered not by time but by intention.

3. Margaret’s Diary — The First Cracks in the Official Narrative

The diary belonged to Margaret Winthrop, the younger sister. Its pages begin with mourning—the funeral of Judge Henry Winthrop in the spring of 1848.

But beneath the grief runs something heavier, something that feels like dread.

Her first entry reads:

“Father’s death closed one door and opened another, but the room beyond feels darker.”

Her apprehension had a name:

Thomas Winthrop.

Her older brother.

Her tormentor.

A failed seminarian who returned to take control of Belelfford Hall with a Bible in one hand and a cane in the other. Margaret describes him entering the house “like an occupying force,” declaring that God had placed him at the head of the family.

Thomas was a zealot of the cruel kind—a man who believed suffering purified the soul and authority was proof of divine favor. Within days of returning, he reorganized the plantation, summoned the enslaved population to the chapel, and delivered a sermon that sounded more like a threat.

According to Margaret:

“His eyes glowed as if he wished the devil to appear just so he could strike him.”

The diary becomes the first primary source to reveal that behind the façade of piety, Thomas installed a regime that was less a plantation than a prison camp:

Leather straps ordered in bulk

Iron manacles brought from Natchez

New locks on nearly every door

And always the sound of his cane tapping across the hardwood floors at night—a metronome of fear.

4. The Yellow Fever Summer

Then came the fever.

Yellow Fever swept the county like an invisible wildfire, striking down enslaved workers first, then house servants, then neighbors. Belelfford Hall became an island of sickness; the field hands died in batches, the air thick with the smell of bile and decay.

Thomas, however, fled.

In Margaret’s words:

“He abandoned us in the night with the speed of a coward and the certainty of a man who believes God will close his eyes to shame.”

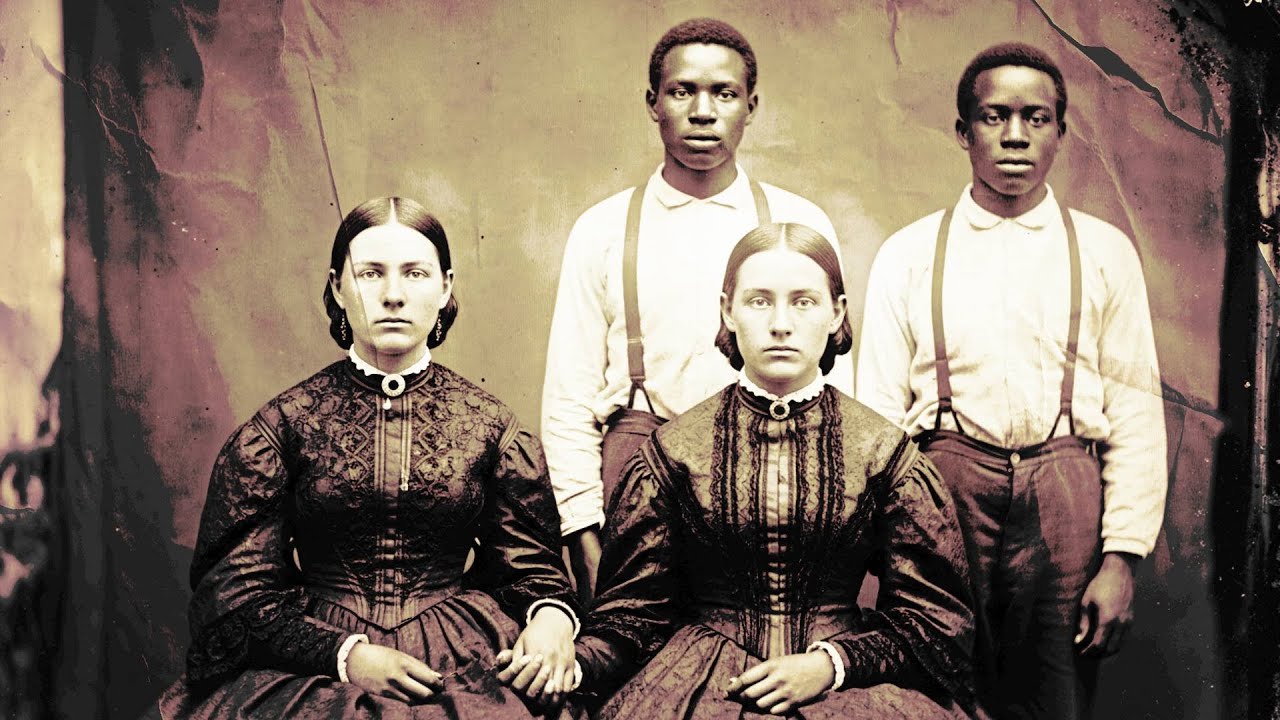

Left behind were:

Claraara

Margaret

And two enslaved men: Josiah and Caleb

The four of them tended the dying, burned soiled linens, and dug graves in soil too dense with summer heat to surrender easily. They survived while sixty others perished around them.

Trauma forged an impossible intimacy.

Disease erased the hierarchy of the plantation in ways no law, no sermon, no master’s whip had ever allowed.

In the claustrophobic isolation of a dying house, lines blurred—first socially, then spiritually.

Margaret’s diary shifts from fear to something almost luminous:

“In death’s shadow we became only four souls, equal in our trembling, bound in our endurance. The world outside had ended, and in its absence a new one quietly began.”

It was here, in the heart of plague and abandonment, that the seed of the blood pact was planted.

5. The Pact Takes Shape

Josiah, quiet and thoughtful, had once secretly learned to read discarded Bible pages. Caleb, gentle and steadfast, was a natural caretaker.

Together they helped Claraara and Margaret stitch Belelfford Hall back to a flicker of life.

Together they prayed—not the prayers Thomas had thundered, but whispered ones of comfort and mercy.

Together they fed one another when the fever stole strength from their limbs.

Margaret’s diary reveals the turning point:

“Josiah said we survived because we were chosen—not by the laws of men, but by God for a purpose.”

In that belief, the sisters found the first spark of their own agency.

They reclaimed the chapel Thomas had polluted with threats and dragged-out sermons.

They cleaned it.

Lit a candle.

Placed flowers on the altar.

And prepared to break a law older than Mississippi itself.

PART II — THE BLOOD COVENANT

1. The Night of the Ceremony

According to Margaret Winthrop’s diary, the night of September 14th, 1848 began with a silence so profound that “even the cicadas seemed to observe it.” The fever had finally burned itself out. The plantation was a graveyard with a house at its center, and in that house were four survivors who had run out of tears before they ran out of fear.

It was Josiah who proposed the ceremony.

It was Claraara who brought the candle.

It was Margaret who brought the parchment.

And it was Caleb who closed the chapel doors.

They had no minister, no witness recognized by law, and no place in society where such a union could exist. So they turned to the only court left to them—the court of the divine, or whatever higher order governed the thin line between survival and oblivion.

Margaret writes:

“We married ourselves in the presence of the dead.”

They stood beneath the cracked wooden cross of the Belelfford Hall chapel, surrounded by pews still marked with fingerprints of the dying who had sought refuge there only weeks before.

Josiah recited from the Song of Solomon, his voice low but steady:

“Many waters cannot quench love, neither can the floods drown it.”

Then each of them pressed a small knife to their thumb, letting blood bead and drip. They signed their names on the two sheets of parchment:

Claraara Winthrop to Josiah

Margaret Winthrop to Caleb

Their blood dried in thick, rust-colored strokes that no historian in 1959 could mistake for ink.

It was a ritual older than scripture, older than any plantation, older than Mississippi itself.

A rebellion disguised as a sacrament.

A covenant forged in grief, sealed in defiance.

But covenants have consequences.

And someone was already on his way home.

2. The Tyrant Returns

The diary falls silent for three days after the ceremony. When it resumes, the tone shifts violently from devotion to dread.

On September 18th, 1848, Margaret writes:

“Thomas is returned. The devil has come home to collect his due.”

He arrived at sunset, gaunt from his travels, reeking of sweat and horse, and radiating the kind of fury reserved for men who believe themselves betrayed by God.

He took in the scene:

the sisters alive

the enslaved men alive

the estate operating without him

the chapel freshly cleaned

a candle stub upon the altar

Margaret recalls his expression as something “between suspicion and revelation,” as if he sensed a crime before he knew its nature.

He separated them at once:

the sisters locked in their rooms

the men dragged to the smokehouse

He interrogated the servants, tore through the pantry, demanded answers from thin air. Margaret writes that he walked the halls with a shaking anger:

“He looked not for sin, but for confirmation of sin.”

And he found it.

Under a loose floorboard in Margaret’s room, hidden poorly in the panic of his arrival, lay the blood-signed certificates.

Thomas did not confront them with his discovery.

He saved that for later.

Instead, he summoned the county physician, Dr. Alistair Finch.

3. Declaring the Sisters Insane

Dr. Finch arrived two days after Thomas’s return, summoned under false pretenses of “grave female hysteria.” What he found were two pale, exhausted women traumatized by plague and captivity—but entirely sane.

Thomas, however, spun the narrative with the skill of a seasoned preacher and the authority of a plantation master.

He told Finch:

the sisters had suffered delusions

they had developed an obsession with the two enslaved men

they claimed to be spiritually “bound” to them

they engaged in “ritualistic fantasies” during the fever

they required confinement for their own safety

Finch, already predisposed to distrust women and defer to men, accepted Thomas’s version.

Within days, he signed a legal petition stating Claraara and Margaret were suffering from “religious hysteria bordering on dementia.”

Thomas gained full guardianship.

A single signature from a county judge sealed the matter.

The sisters’ voices were erased by law.

Their truth dismissed as madness.

Their love criminalized as sin.

4. The Murder of Caleb

The worst chapter in the diary is written in a frantic, slanted hand, as if Margaret’s entire body shook while writing.

The entry is dated October 12th, 1848.

It reads:

“Tonight he took Caleb to the smokehouse. He said sin must be scourged from this land. He made us listen. We heard what he did.”

The screams lasted three hours.

Then silence.

Then the sound of something heavy dragged across the dirt.

Margaret’s handwriting collapses into smudges. Her final sentence:

“Caleb is with God now.”

The next day, the official coroner’s report recorded Caleb’s death as “fever of the blood”—a euphemism for tortured to death. The report was countersigned by Thomas himself.

It was the perfect plantation lie:

A Black man does not die from cruelty.

He dies from “fever.”

No further questions.

By the end of that week, Josiah was sold to a Louisiana trader known for sending enslaved people to sugar plantations—death camps by another name.

Thomas believed he had killed one and banished the other.

He believed the covenant was broken.

He believed God was once again his ally.

He believed wrong.

5. Silence in the House of Locks

With Caleb dead and Josiah gone, the sisters entered a silence so profound it frightened even Thomas. The diary entries stop. What remains is the evidence from Thomas’s own account books, preserved in county ledgers:

He bought bars for the sisters’ windows

He reinforced his own bedroom locks

He purchased an aggressive guard dog

He avoided town

He slept with a pistol under his pillow

He stopped tithing to the church

He patrolled the house at night with a candle, muttering scripture

This was not a man triumphant.

This was a man haunted.

He had destroyed his sisters’ world.

He had erased their love.

He had killed a man.

But something gnawed at him.

Something he could not name.

6. The Hidden Manuscript — Josiah Lives

The second source that completes the story emerged in 1903, when a researcher uncovered an anonymous abolitionist memoir stored in a church basement in Natchez.

Its most shocking revelation was simple:

Josiah survived.

Freed when abolitionists intercepted the slave coffle headed for Louisiana, he refused sanctuary in the North.

The manuscript quotes him:

“My body is free, but my soul is buried in Mississippi. I made them a promise in blood. I will finish it.”

He told the abolitionists everything:

the fever

the love

the ceremony

the murder

the sale

the sisters’ imprisonment

And the abolitionists, far from stopping him, agreed to help.

They saw his mission not as vengeance, but as justice.

The manuscript calls Thomas Winthrop:

“A sickness. A blasphemy. A rot in human form.”

And Josiah:

“The cure.”

It details preparations that read like the script of a clandestine war:

contacting the sisters through a free Black herbalist

smuggling messages in dried leaves

drugging the guard dog

weakening window latches

studying Thomas’s habits

waiting for the first snowfall to silence footsteps

And most chilling:

Josiah spent days preparing a leather whip, soaked in brine—the same method Thomas used on Caleb.

The instrument of punishment would become the instrument of justice.

The manuscript calls it:

“a holy reversal.”

A final sermon delivered in leather and blood.

7. The Night of Reckoning

The sheriff’s report from December 21st, 1848 tells the official version:

Thomas Winthrop found dead in his bed, body covered in lash marks.

Window latch broken.

House quiet.

Sisters calm, “detached,” speaking of an “angel of the Lord.”

The sheriff dismissed their testimony as madness.

He filed it as an unsolved crime.

But the abolitionist manuscript finishes the story:

Josiah returned at dawn to the safe house in Natchez, clothes bloodied, hands trembling not with fear—but with completion.

He had kept his covenant.

He had made Thomas listen to the judgment he once forced onto Caleb.

And before leaving Belelfford Hall forever, he did one last thing.

He dug up Caleb’s body and carried his remains north.

The manuscript ends with:

“He would not leave his brother in cursed ground.”

8. The Aftermath — Two Ghosts in a Ruined House

Claraara and Margaret lived another sixteen years.

Locked away.

Declared insane.

Considered harmless.

Forgotten by everyone except one another.

When Union troops passed through in 1864, a fire consumed the main house. The sisters were found in the chapel—the same chapel where they had made their blood pact—lying side by side, hands clasped, dead from smoke inhalation.

They died as they lived:

Bound to one another.

Bound to their love.

Bound to their truth.

And the iron crucifix found in the 1959 trunk bears the final testament:

Four names engraved into the arms of the cross:

Claraara

Margaret

Josiah

Caleb

A church of four.

A covenant unbroken.

A family forged not by birth, but by blood, sacrifice, and rebellion.

PART III — THE GHOSTS LEFT BEHIND

1. A Silence That Wasn’t Madness

After Thomas Winthrop’s brutal death in December 1848, Adams County settled quickly into its preferred narrative:

Two mad sisters.

A violent intruder.

A tragic, unsolved crime.

Everything fit neatly into a box labeled “Local Misfortune—Do Not Open.”

But the official version ignored the details that didn’t fit:

The sisters’ calm demeanor

Their identical statements about an “avenging angel”

The precise way the window latch had been pried open

The guard dog found barely conscious

The lack of forced entry into the main house

The strange peace on the sisters’ faces

And the most glaring:

no valuables were stolen.

Whoever killed Thomas had come not to rob, but to sentence.

The county sheriff chalked the sister’s statements up to hysteria, the way men of that era dismissed any inconvenient truth spoken by a woman—even more so two women already branded unstable.

But in hindsight, historians see what the sheriff could not:

The Winthrop sisters were not mad.

They were keeping a secret.

Protecting a man.

Preserving a covenant.

Carrying the final burden of a crime they believed was just.

2. The Reconstruction of a Quiet Rebellion

As the years passed, the story of Belelfford Hall faded everywhere except in the memory of the county’s Black community, who preserved it in fragments:

A whisper about a “vengeful spirit”

A rumor about a master judged “by God Himself”

A tale of two white women who were “not like the others”

A story of a man who “escaped chains but went back for justice”

These were not just folktales.

They were oral footnotes to a hidden truth.

Historians, piecing together the timeline from Margaret’s diary and the 1903 abolitionist manuscript, argue that the sisters understood exactly what was happening the night Thomas died.

They had orchestrated it.

Not the murder itself—Josiah alone carried that burden.

But the access.

The timing.

The weakened locks.

The drugged dog.

The open chapel door.

In their own way, the sisters acted as gatekeepers of the covenant.

That is why they remained silent afterward.

Not from madness.

But from allegiance.

Their silence was not erasure.

It was loyalty.

A final act of love.

3. The Slow Death of Belelfford Hall

The years between 1848 and 1864 are sparsely recorded but deeply evocative.

Plantation ledgers record only decay:

fields unplowed

barns collapsing

orchards dying

fences rotting

taxes unpaid

Neighbors rarely visited.

The sisters never left.

Food was brought by a single elderly servant.

The estate lived in a strange half-life, untended and unclaimed—like a house waiting for ghosts.

By 1855, Belelfford Hall was already described in county papers as:

“a grand ruin inhabited only by two unfortunate ladies.”

Plantation gossip transformed Claraara and Margaret into boogeywomen used to frighten children:

“Eat your supper or the Winthrop sisters will come for you.”

“Mind your manners or you’ll end up mad like the women at Belelfford.”

“Don’t wander near the old chapel—it’s cursed.”

It was easier for the county to call them witches than survivors.

Easier to mock them than face the truth.

Easier to blame their madness than acknowledge the horror that had unfolded in the smokehouse and bedroom of the great house.

Belelfford was collapsing physically, but spiritually it had already fallen.

Its rot was the rot of a crime that no one dared speak.

4. The Sisters’ Final Day

The end came during the Civil War, on January 3rd, 1864, when Union skirmishers were spotted moving along the river. Townspeople fled inland. Plantations shuttered. Fires broke out across Adams County—some accidental, some intentional, some blamed on soldiers, others blamed on slaves making a run for freedom.

A blaze was reported at Belelfford Hall.

Newspaper accounts describe a “conflagration engulfing the east wing,” but what mattered was not the burning wood.

It was what the soldiers found in the chapel.

The Winthrop sisters lay side by side:

hands clasped

bodies unburned

faces calm

lungs filled with smoke

They had died together, the way they had lived:

in the place where the covenant was born.

The chapel, untouched by fire until the very last collapse of the roof, became their tomb.

By morning, the estate was a smoking shell.

By spring, it was abandoned.

By Reconstruction, the Winthrop name had faded into a local embarrassment.

And by the turn of the 20th century, the family’s story was little more than a cautionary tale told by elders who did not know its true origin.

5. The Iron Crucifix — A Relic of a Hidden Religion

The last and most haunting artifact found in the 1959 trunk was not the diary, nor the parchments.

It was a small iron crucifix—crude, uneven, hand-forged.

Four names scratched onto the arms:

Claraara

Margaret

Josiah

Caleb

A family that never existed in law.

A church that never existed in records.

A sacrament that never existed in the eyes of Mississippi.

And yet, it existed enough for someone—perhaps one of the sisters, perhaps even Josiah before his final departure—to etch those names into iron.

Not wood.

Not paper.

Iron.

Something meant to endure.

Historians debate its purpose:

A memorial?

A confession?

A secret symbol of their covenant?

A religious relic of their own making?

But its meaning, in the context of the diary and manuscript, becomes clear:

It was their creed.

Their faith.

Their proof that love could exist in the ruins of slavery, cruelty, plague, and patriarchal law.

A heresy in Mississippi.

A sanctity in the eyes of those who survived.

6. The Fire That Freed the Truth

The 1864 fire destroyed nearly everything:

letters

account books

household records

personal papers

legal documents

Had the trunk not been hidden beneath the chapel floor—iron-bound and buried beneath decades of dust—none of the truth would have survived.

Even then, the county tried to hide it.

The demolition crew might never have reported the find if not for a historian who happened to be present and insisted the trunk be opened under supervision.

Once the blood signatures were verified, it became impossible to bury the discovery again.

The truth rose from the ashes of Belelfford Hall like a specter demanding recognition.

7. What Adams County Chose to Forget

Why did no one speak of the sisters’ true story for more than a century?

The answer lies in guilt.

Because the county had:

accepted Thomas’s rulership

ignored the screams from the smokehouse

signed off on fraudulent coroner’s reports

allowed the sisters to be declared insane

refused to investigate his death

buried the truth under gossip and folklore

Acknowledging the true story required acknowledging complicity.

And in the Jim Crow South, no white community had any interest in admitting it once allowed two women to marry enslaved men in defiance of every law and every prejudice of their time.

It was easier—safer—to reduce the sisters to madwomen.

To reduce Josiah to a vengeful ghost.

To reduce Caleb to a footnote.

To reduce a covenant to a legend.

To reduce justice to a crime.

The county didn’t forget.

It chose to forget.

8. The Spirits That Never Left

Even today, locals claim strange phenomena around the ruins of Belelfford Hall:

the smell of woodsmoke on windless nights

the faint sound of metal striking flesh

the whisper of two women singing a hymn

a flicker of candlelight in the old chapel foundation

footsteps crunching gravel where no one stands

Folklorists argue these stories are cultural memory—

the land remembering what people tried to erase.

Historians argue they are metaphor.

Locals swear they are literal.

But all agree the story of the Winthrop sisters, once unearthed, refuses to die.

The ground remembers.

The ruins remember.

Mississippi remembers—even when it won’t speak.

9. A Covenant That Outlived Its Makers

What happened to Josiah afterward remains one of the great unanswered questions.

The 1903 manuscript says he took Caleb’s remains north.

After that, he vanishes from all known records.

Did he remarry?

Did he have children?

Did he ever whisper the truth to anyone?

Did he carry the crucifix?

Did he ever return to the South?

We do not know.

All that remains is one line from the abolitionist’s final note:

“He carried no guilt. Only a promise fulfilled.”

And perhaps that is enough.

The sisters left no heirs.

Josiah left no recorded descendants.

Caleb’s grave—wherever Josiah reburied him—remains unknown.

And yet the covenant they formed has outlived all of them.

The diary, the certificate, the crucifix—

they form a kind of scripture of their own.

A testament to a faith the world refused to recognize.

A church built of love and defiance.

A family created in blood and courage.

A tragedy that became a myth.

A myth that became a truth.

A truth that, when finally excavated, forces us to confront the realities the Old South buried beneath magnolias and marble.

10. The Final Unanswered Question

Every investigative story ends with something unresolved.

In this case, it is not the murder.

Not the motive.

Not the chain of events.

Not the pact.

Not the love.

All of that is clear.

What remains is a question far more unsettling:

Did the covenant end with their deaths?

Or does it—in some form—still linger in the ruins?

Was their act of rebellion a moment in time?

Or the founding of a hidden church, a cultural scar, a moral echo that never entirely fades?

Does the iron crucifix represent closure?

Or continuation?

Does their pact live on in the stories still whispered today?

In Mississippi, where the past is never past, who is to say the covenant is finished?

EPILOGUE — THE HISTORY MISSISSIPPI TRIED TO BURY

The story of the Winthrop sisters is not just a Gothic tragedy.

It is an indictment.

A revelation.

A resurrection.

A reminder that the South’s official histories are often works of fiction—

crafted, curated, sanitized.

Beneath those stories lie others:

Stories of love forbidden by law.

Stories of cruelty sanctioned by scripture.

Stories of rebellion buried by fear.

Stories of justice carried out by the powerless.

Stories of women dismissed as mad because they told the truth.

Stories of men erased because they were enslaved.

Stories of covenant, sacrifice, courage, and vengeance.

Stories that survive in diaries, in folklore, in iron crucifixes, in the soil itself.

Stories like this one.

The Mississippi Sisters Who Married Their Slaves: The Hidden Pact of 1848

is not merely a tale of murder and rebellion.

It is a narrative of resistance.

A record of forbidden humanity.

A haunting reminder that even in the deepest chambers of oppression,

people still found ways to love, to defy, to avenge, and to remember.

The past is not quiet.

It is buried, waiting.

And it calls to those willing to listen.