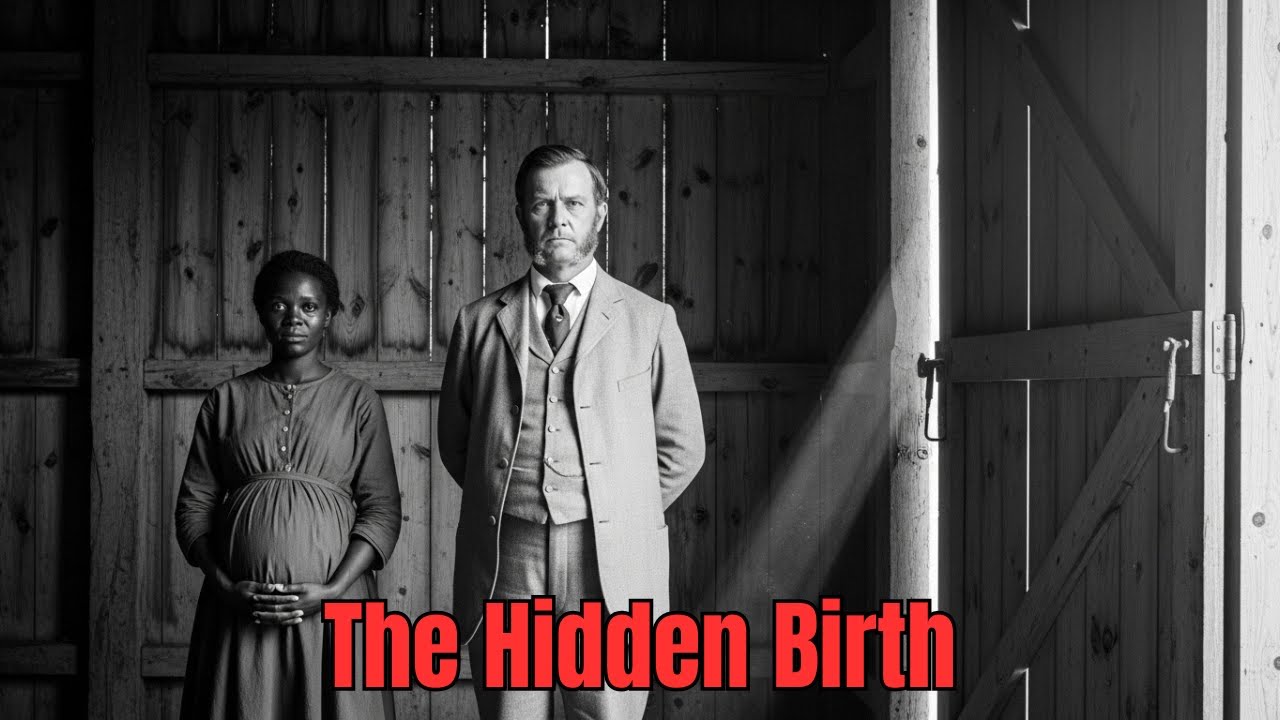

(Photo 1850) The Master Bought This Pregnant Slave… The Birth Certificate Revealed Her Previous | HO!!!!

(Photo 1850) The Master Bought This Pregnant Slave… The Birth Certificate Revealed Her Previous | HO!!!!

In the autumn of 1850, in a courthouse 70 miles south of Memphis, a clerk dipped his pen in ink and made a notation that would outlive every man in the room. He didn’t know it then, but that small, almost careless act of documentation would become one of the most haunting pieces of evidence in the history of American slavery — a single line that would expose a network of crimes hidden in plain sight for more than 170 years.

The auction that day in October looked like every other: wagons of supplies, livestock, and, at the center of it all, human beings. Among them was a young woman named Sarah, visibly pregnant, estimated to be around twenty-two years old. The bidding was brisk. The buyer, a local plantation owner named Richard Whitmore, paid $850 — a high price that reflected both Sarah’s youth and the unborn child she carried.

No one in that courthouse could have guessed that Sarah’s name, scribbled in a county ledger, would one day spark an investigation that would shake the comfortable myths of the antebellum South — or that the faint, fading handwriting of a clerk would become the key to uncovering one of the South’s most tightly guarded secrets.

The Birth That Should Have Been Routine

Whitmore’s Oakmont Plantation, twelve hundred acres of cotton and tobacco, sat in a quiet Mississippi county where the sound of cicadas drowned out the cries from the fields. On October 16th, 1850, Sarah arrived there — unnamed beyond her first name, assigned to a cabin shared with three other women. The overseer’s notes were typically cold and perfunctory: new acquisition, fieldwork suspended pending birth.

Six weeks later, on the morning of November 28th, Sarah went into labor. The plantation midwife, Ruth, an older enslaved woman who had delivered more than fifty babies over her lifetime, attended her. At dawn, a healthy baby boy was born. He cried, strong and loud, the sound of life entering a world that refused to see him as human.

Whitmore, for reasons no one could explain, summoned the county clerk to Oakmont that same afternoon. Enslaved births were rarely documented formally. But Whitmore insisted. The clerk, a man named Henderson, arrived with his ledgers and sealed papers. He filled out the standard information:

Child’s name: Thomas

Mother: Sarah

Owner: Richard Whitmore

But then Henderson did something unusual. On a separate line — one that did not appear in any template — he added:

Previous ownership documented per maternal records: Judge Marcus Thornhill.

That single notation would sleep in the courthouse archives for nearly two centuries, its meaning hidden in plain sight.

The Judge Who Owned No Slaves

In 1850, Judge Marcus Thornhill was one of Mississippi’s most prominent men. He presided over the county circuit court, ruled on property disputes, and prided himself on his reputation as a man of law and Christian integrity. He also, very publicly, denied ever owning slaves.

“I defend the constitutional rights of property owners,” he wrote in an 1848 letter published in The Natchez Democrat. “But I myself hold no such property. My wealth derives from law and commerce, not bondage.”

It was a claim repeated in sermons, dinner parties, and editorials. It helped Thornhill maintain respectability among both pro-slavery businessmen and the Northern investors who financed the region’s railroads. But census records told a different story. The 1840 census listed four enslaved individuals under his household. By 1850, that number dropped to zero. On paper, he had freed them — or sold them.

In reality, as later research would reveal, he had found a different way to profit from human bodies.

The Breeding Network

The notation on Sarah’s birth record didn’t make sense at first glance. Why would the name of a judge appear as “previous owner” of a pregnant woman sold by another man? Why would Whitmore, who purchased her, ask for a formal birth certificate at all?

The answer, historians would later conclude, was as simple as it was horrifying: because both men were partners in a network that turned enslaved women’s pregnancies into profit.

Between 1840 and 1860, records across multiple counties revealed the same pattern: pregnant women purchased at auction, transferred to plantations connected to Thornhill’s associates, and resold soon after giving birth. The children remained property of the final owner. The women were moved again, traded, or “leased,” as the euphemism went.

Financial ledgers disguised it as commerce. Court documents, business partnerships, and railroad investments provided cover. It was a closed loop of men — planters, judges, lawyers — who used the law to launder human life into wealth. They called it “natural increase.” In truth, it was organized rape and forced reproduction.

And Sarah, purchased by Whitmore in 1850, had been part of it.

A Child Born into Silence

Thomas grew up at Oakmont knowing nothing of the system that created him. By the time he was seven, he was working in the fields. By twelve, he was harvesting cotton from dawn to dark. He never learned to read. He never saw the document that bore his name.

His mother, Sarah, gave birth to two more children — both girls — before dying in 1859. She was buried without ceremony in a patch of earth beyond the fields, where the graves of the enslaved were marked only by memory.

Thomas survived the Civil War and emancipation, taking the surname Freeman. But freedom was a word without land, without money, without justice. He sharecropped the same fields where he’d once labored in chains, trapped in debt that would last his entire life. He died in 1914, never knowing the truth about his birth.

The birth certificate stayed locked away, a ghost in the archives.

The Genealogist

It would take 169 years before someone stumbled across that ghost again.

In 2019, a retired Detroit schoolteacher named Patricia Freeman Johnson began tracing her ancestry through DNA databases. Her father, a history professor, had spent years talking about Mississippi, about a family story of a “judge named Thornhill” that no one could explain.

Patricia’s search started on Ancestry.com, like millions of others. But the results were startling. Her DNA matched multiple people with the surname Thornhill — descendants of the same Mississippi judge whose name her family had whispered about for generations.

At first, she thought it was coincidence. Then she found it: the 1850 birth record in the county courthouse, its ink faded but legible. “Child’s name Thomas. Mother Sarah. Owner Richard Whitmore. Previous ownership documented per maternal records — Judge Marcus Thornhill.”

Patricia sat in her rental car outside the courthouse for twenty minutes, staring at the photocopy she’d paid three dollars for.

There it was — the proof her family’s oral history had carried for more than a century. And the beginning of a story that would consume the next five years of her life.

The Historian

Patricia brought the document to Dr. Elena Martinez, a historian at the University of Mississippi specializing in slavery and forced reproduction. Together, they began piecing together a puzzle the country had never wanted to see.

They found at least seventeen pregnant women who passed through Thornhill’s and Whitmore’s hands between 1840 and 1860. All were purchased while pregnant. All gave birth within months. The timing, the transactions, the payments — everything matched a deliberate system. Financial records described payments to Thornhill as “consultation fees,” though no legal work was documented.

When Martinez published her findings in The Journal of Southern History in 2020, the reaction was explosive.

Thornhill’s descendants called it slander. They hired lawyers, claiming the evidence was “circumstantial.” But the DNA didn’t lie. Patricia’s family was biologically connected to Thornhill’s.

For Patricia, the discovery wasn’t just academic. It was personal. “My great-great-grandfather was born into a crime,” she said in an interview. “The judge who wrote the law also wrote the conditions of his mother’s suffering.”

Two Families, One Bloodline

In 2021, Patricia convinced several relatives to take additional DNA tests. The results revealed even more. Thomas Freeman’s direct male descendants shared a Y-chromosome match with the male line of the Thornhill family — an unbroken genetic signature passed from father to son.

It meant that Judge Marcus Thornhill was almost certainly Thomas’s biological father.

The truth was brutal. The judge had impregnated Sarah, then sold her — pregnant — to his business partner to hide the evidence. The notation “previous ownership documented per maternal records” wasn’t bureaucratic error. It was a whispered acknowledgment by a clerk who had seen too much.

Patricia wrote to Thornhill’s white descendants. Most ignored her. One, however, responded.

The Descendant

Rebecca Thornhill Morrison, a 68-year-old woman in Atlanta, had grown up in a family that idolized the judge. Her father had named his law firm after him. There was a portrait of the judge hanging above the fireplace.

When Patricia sent her the documents — the birth record, the DNA data, the financial ledgers — Rebecca was silent for days. Then she called.

“I don’t know what to say,” she told Patricia. “Everything I was taught about him — it’s all wrong.”

The two women spoke for hours, trading family stories separated by blood and history but bound by the same lineage. Rebecca admitted that her siblings didn’t want to hear it. “They think you’re trying to destroy our name,” she said. “But I think the truth matters more.”

In 2022, Rebecca published an open letter in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution:

“I am a direct descendant of Judge Marcus Thornhill of Mississippi. Recent genealogical evidence shows that my ancestor participated in the forced breeding and sale of enslaved women. I cannot undo his crimes, but I can acknowledge them. Silence is complicity.”

The letter split her family apart. Her father refused to see her. But it opened a floodgate of truth.

The Lawsuit

By 2023, Patricia and Rebecca had connected with forty-seven living descendants of the seventeen women exploited in the Thornhill–Whitmore network. Together, they filed a lawsuit: Freeman et al. v. Thornhill Estate et al., demanding acknowledgment and restitution.

Legal experts predicted immediate dismissal. But in July 2024, Judge Sarah Washington — herself a descendant of enslaved Mississippians — issued a ruling that stunned the legal world. She allowed the case to proceed.

“For the first time,” she wrote, “this court recognizes that the economic fruits of slavery are not abstract or historic. They are traceable, tangible, and in some cases, still held by the descendants of those who profited from them.”

The ruling was narrow but unprecedented. It dismissed claims against the federal and state governments, but allowed the unjust enrichment claims against the Thornhill Family Trust and the Whitmore Agricultural Corporation to continue.

It was the first slavery-related reparations case in U.S. history to survive a federal motion to dismiss.

The Discovery

Through court-ordered discovery, Patricia’s attorneys obtained access to the Thornhill family’s private archives. What they found was devastating.

A handwritten journal, kept by Judge Thornhill himself between 1845 and 1872, contained explicit references to “arrangements” with planters — coded language for the buying and impregnating of enslaved women, and the shared profits from the sale of their children. In one passage dated April 1850, he wrote:

“R.W. [Richard Whitmore] and I have agreed to transfer Sarah before term, ensuring no confusion in accounts. Better this way — keeps the matter discreet.”

The words were careful, clinical. But the meaning was unmistakable. The “matter” was a human being. The discretion was the concealment of a child he had fathered through rape.

Financial ledgers confirmed what the journal implied: Thornhill received “consultation fees” every time a child was born on a partner’s plantation. Each “fee” was calculated at roughly half the market value of a newborn child.

The system was more organized than anyone had imagined — not isolated acts of cruelty, but a network of profit, paperwork, and secrecy.

The Reckoning

In August 2023, descendants from both families gathered near the site of Oakmont Plantation, now a soybean field. They unveiled a memorial: a bronze marker inscribed with 19 names — Sarah, Thomas, and the seventeen other women whose lives had been stolen for profit.

Rebecca stood beside Patricia as they read aloud the inscription.

“Their names were erased, their bodies commodified, their children sold. We remember them.”

It wasn’t reconciliation. It was acknowledgment — the first step toward truth.

When reporters asked Rebecca what it felt like to stand there, she said, “My family built wealth on their pain. I can’t change the past, but I can stop pretending it didn’t happen.”

Patricia added, “My ancestors were silenced. Now, at least, someone is listening.”

What the Birth Certificate Meant

The birth certificate that started it all now sits under glass at the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum in Jackson. The ink is faint, the paper browned with age. But the line that changed everything is still visible:

Previous ownership documented per maternal records — Judge Marcus Thornhill.

To most people in 1850, it meant nothing. To the descendants who found it 169 years later, it meant everything.

It was proof that history’s silences could be broken — that the truth, once buried, still has a pulse.

Epilogue

As of 2025, Freeman v. Thornhill Estate remains in litigation. The outcome is uncertain. But the case has already changed the conversation. Law schools are teaching it. Other families are beginning to search their archives.

Every few weeks, Patricia receives messages from strangers who’ve found similar documents — birth records, sale ledgers, notations no one noticed before. Each one another fragment of a story that America is still learning how to face.

When she looks at the photocopy that started it all, Patricia says she sometimes imagines the clerk who wrote that extra line in 1850. “He couldn’t stop what was happening,” she says softly. “But maybe, just maybe, he knew one day someone would read it.”

A single line of ink, meant to disappear, became a confession that refused to die.

And after 170 years, it finally spoke.