Iowa 1952 cold case solved — arrest shocks community | HO!!

Iowa 1952 cold case solved — arrest shocks community | HO!!

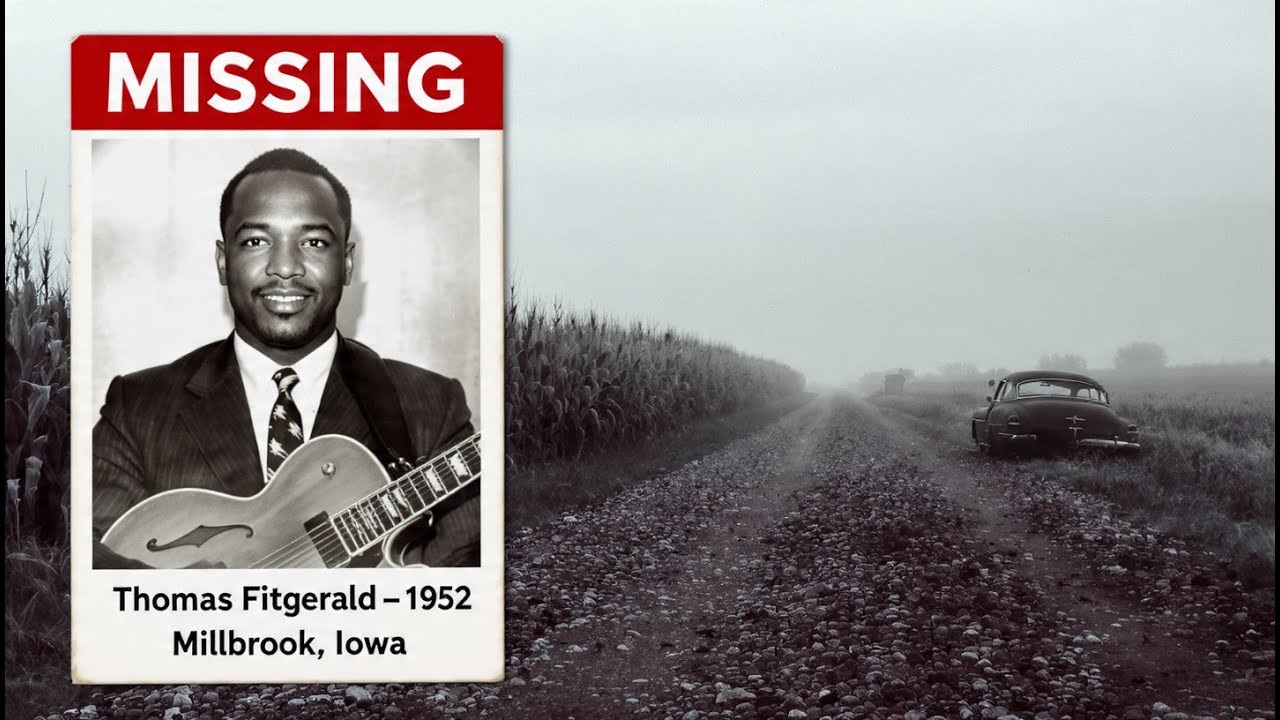

The Forgotten Musician

On a fog-soaked September morning in 1952, a farmer driving along County Road 7 near Millbrook, Iowa, spotted something strange. A green 1948 Ford Deluxe sat idle at the edge of a cornfield, its driver’s door ajar like a mouth mid-scream. The engine was cold, the keys still dangling from the ignition. On the passenger seat rested a fedora, neatly placed. In the backseat lay an open, empty Gibson guitar case.

Deputy Frank Marino, a man accustomed to small-town disputes and stolen livestock, knew right away something wasn’t right. The missing owner of the car was Thomas Fitzgerald, a 32-year-old blues guitarist from Chicago’s South Side, last seen performing a packed show at the Rusty Nail Tavern the night before.

By all accounts, Fitzgerald had electrified the crowd — his playing smooth, mournful, alive with something Millbrook had never heard before. Then, as suddenly as a song fading out, he vanished.

Theories came fast. He’d run off with a woman. He’d skipped town over debts. Maybe he’d just decided to disappear. But for one deputy — and for one sister waiting by a telephone in Chicago — it was clear that something much darker had happened.

The Night the Music Died

The Rusty Nail was the kind of place where men drank to forget and women pretended not to see. The air was thick with smoke, sweat, and country beer. On that night, Fitzgerald had been the anomaly — a Black musician commanding a room of white farmhands and factory workers in the heart of 1950s Iowa.

Among the crowd was Margaret Hoffman, a farmer’s wife with red hair curled like a movie star’s and a green dress she’d ironed twice. She came with her husband, Gerald, who worked long hours at the grain elevator and spoke few words even at home.

But as Fitzgerald played, Margaret’s eyes betrayed her. The way she leaned forward, the way she smiled — it was enough for her husband, and for one other man, to notice.

That man was Vincent Bauer, a 40-year-old war veteran turned tavern security guard — broad-shouldered, feared, and broken by something he’d brought back from the Pacific. Bauer had been watching Margaret for months. And that night, when she smiled at another man, something inside him snapped.

After the show, Fitzgerald packed his Gibson, collected his pay, and left around 2 a.m. Witnesses saw him walk alone to his car. The last man to speak with him — or so he claimed — was Bauer.

A Case Left to Die

By sunrise, Fitzgerald’s car sat abandoned three miles from town. No signs of struggle. No footprints. No blood. Just a void where a man should have been.

Deputy Marino spent weeks chasing leads. He questioned the tavern owner, Eugene Walsh, who claimed ignorance. He spoke to Margaret Hoffman, who seemed frightened but evasive. He questioned Bauer twice — both times met with calm indifference.

Marino found what he believed to be evidence — a torn piece of blue cloth snagged in an old barn near the Keller property, and a patch of soil stained dark. He sent samples to Des Moines for testing. When results came back, his worst suspicions were confirmed: the soil contained human blood.

But in 1952 Iowa, not all victims were equal. The sheriff’s office dismissed Marino’s findings, labeling the case a “voluntary disappearance.”

Fitzgerald was Black, a musician, an outsider. The county saw no reason to waste resources on “someone who didn’t belong.”

Marino never forgot. He kept the evidence envelope in his desk for decades, long after the case was buried — both figuratively and, as time would prove, literally.

Sixty-Six Years of Silence

Life went on. The Rusty Nail kept serving beer. The Kellers’ barn collapsed in a 1964 storm. Fitzgerald’s sister, Dorothy, called the sheriff’s office every September 14th until her death in 1982.

By the time Marino died in 2010, his memory fading, he was still talking about “the guitar player in the barn.” No one listened.

It wasn’t until March 2018 — sixty-six years later — that the ground finally gave up its secret.

Construction crews breaking soil for a boutique hotel on the old Keller property struck something solid: human bones. At first, they thought it might be pioneer remains. Then they found a corroded harmonica — Hohner brand, key of C — and fragments of 1950s-era fabric.

Forensic anthropologist Dr. Rebecca Tanaka of the Iowa Division of Criminal Investigation confirmed what history had refused to acknowledge: it was homicide. The skull showed multiple fractures consistent with blunt-force trauma. Defensive wounds on the left forearm suggested the victim had seen his killer coming.

DNA testing identified the remains as Thomas Fitzgerald.

Reopening the Wound

The discovery made headlines across the Midwest: “1952 Cold Case — Musician’s Remains Found.”

Sheriff Michael Doyle, grandson of one of the original deputies, reopened the investigation. He brought in Detective Sarah Navarro, a cold-case specialist known for solving the unsolvable.

They pieced together what little survived: Deputy Marino’s faded notes, photographs, and the torn cloth still sealed in its evidence envelope. The picture that emerged was both tragic and familiar — a talented Black artist in a white town, a jealous husband, a possessive bouncer, and a community that looked away.

When Navarro tracked down Margaret Hoffman, now 82 and living in Cedar Rapids, the old woman trembled as she spoke.

“I was young,” she said. “I smiled at him, and that smile was a death sentence in 1952 Iowa.”

She remembered Bauer’s expression that night — the fury behind his eyes — and a chilling encounter days later in a grocery store aisle.

“He told me, ‘That musician you liked — he made it back to Chicago just fine. Probably best he doesn’t come back this way.’”

That was all she needed to know.

The Confession

On April 19, 2018, police arrested 91-year-old Vincent Bauer at his home on Oak Street. He answered the door in a cardigan and slippers, a walker between him and the past.

When Detective Navarro sat across from him in the interrogation room, she didn’t press. She waited. After forty-seven minutes of silence, the old man exhaled and began to speak.

“I didn’t plan it,” he said. “Not that night. But when she smiled at him — the way she smiled — I knew what it meant. I followed him. Told him his tire looked soft. He pulled over, trusting me. I came up behind him with a tire iron.”

Three blows to the skull. One defensive wound. One body dragged into an abandoned barn. One guitar thrown into the Des Moines River.

“I buried him in the corner,” Bauer said. “Smoothed the dirt. Thought it would be over.”

It wasn’t. For 66 years, the truth slept beneath the soil.

Justice — Too Late for the Living

When the trial began in October 2018, reporters packed the old county courthouse. The image was surreal: a frail nonagenarian defendant, oxygen tank at his side, being tried for a murder committed when Harry Truman was president.

Bauer pleaded not guilty. His public defender argued dementia, confusion, coercion — but the taped confession was damning.

The jury deliberated six hours before convicting him of second-degree murder. He was sentenced to 25 years in prison, though everyone in the courtroom knew he would never live that long.

From her seat in the third row, Margaret Hoffman wept.

“I smiled at a man just doing his job,” she told reporters outside the courthouse. “And that smile killed him.”

The Music Returns

The Chicago Tribune ran a front-page feature on Fitzgerald — “The Bluesman Iowa Forgot.” Musicians on the South Side held a tribute concert, playing the songs he’d once performed in smoky taverns.

A record collector unearthed three surviving acetates from 1951 — Fitzgerald’s scratchy, soulful voice cutting through decades of silence. They were remastered and released online, streamed thousands of times by people who’d never known his name but felt his story in every note.

In October 2018, Fitzgerald’s remains were laid to rest at Burr Oak Cemetery in Chicago, alongside other blues legends. More than 200 people attended, most strangers connected only by outrage and reverence. Among them, quietly in the back, was Margaret Hoffman. She didn’t speak — she just listened as a young guitarist played “Sweet Home Chicago.”

Epilogue: The Plaque and the Price

Vincent Bauer died in prison on January 11, 2019 — just three months into his sentence — from congestive heart failure. His final recorded words to a researcher studying cold cases were chillingly devoid of regret:

“Back then, what I did made sense. It protected the order of things.”

Justice had come, but decades too late to matter to anyone it should have saved.

Today, the boutique hotel that stands where Fitzgerald was buried has a bronze plaque in its lobby:

“Near this site, Thomas Fitzgerald, musician, was laid to rest in 1952.

Discovered 2018. Remembered always.”

Most guests don’t notice it. They check in, talk about meetings and weather, sip coffee over their phones. Few pause long enough to imagine a young Black musician playing his last song in a town that wasn’t ready for him — or the cold Iowa night that swallowed him whole.

Because in Millbrook, like in much of America, the earth remembers even when people choose to forget.