His enslaved wife died trying to escape — then the white man met true terror in the American South | HO!!!!

His enslaved wife died trying to escape — then the white man met true terror in the American South | HO!!!!

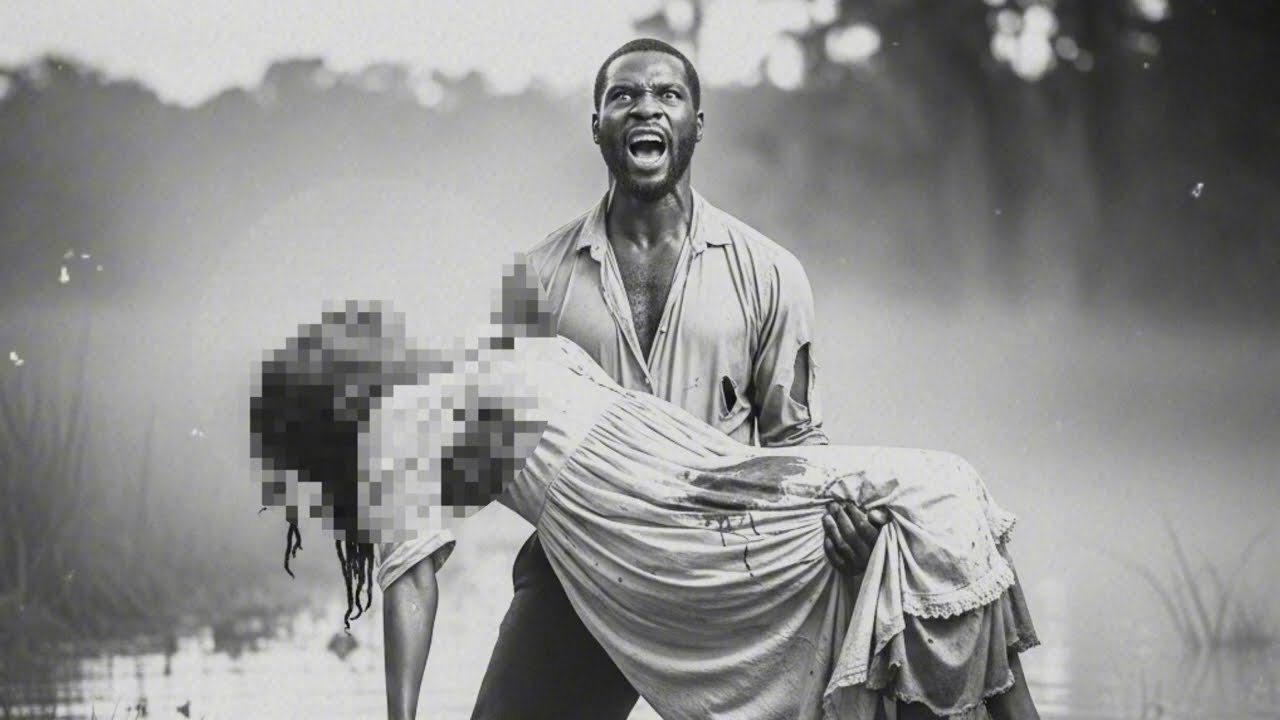

PART I — The Death That Broke Thornwood

The night was moonless when Marcus held his wife’s body against his chest. The cabin smelled of smoke and damp soil, and the air had the oppressive stillness that follows a storm—or precedes one. Everything was quiet now. Too quiet. Sarah’s breathing, once ragged, had already thinned into silence. Her warmth was escaping rapidly, as if life itself were in a hurry to abandon the room. When Marcus brushed the hair from her face—hair still matted from the “example” the plantation demanded—he realized she was already gone. Her eyes stared not at him but upward, past the thatched roof, toward something far beyond Thornwood.

What escaped Marcus’s throat was not merely a cry of grief. It was a sound that tore through the stillness like a fault line splitting open. A scream that carried the unsayable: the humiliation of being forced to stand helpless among rifles, the memory of her voice apologizing for failing to reach the river, the knowledge that her last living moments were shaped by men who believed suffering was a form of management.

That scream split him open. And when it ceased, something inside Marcus closed forever.

This is the story of what happened next—how a world built on domination met a force it was not prepared for. It is the story of a man who stepped into a swamp with no intention of surviving… and emerged with a purpose the South would never forget.

But to understand the terror that would eventually spread across three counties, one must begin three days earlier—while Sarah was still alive, still smiling, still imagining the river as a doorway to another world.

The Last Good Morning

Before Sarah Thorn died, those who knew her said she carried a kind of quiet hope that seemed impossible for someone in her position. “She always looked like she had a plan,” recalled Josephine Rankin, whose great-grandmother lived on the neighboring plantation. “Like she believed there was more to life than the fields. Like she could see something the rest of them couldn’t.”

On that final morning, the sun had risen orange over the cane fields. Sarah and Marcus had only a few stolen minutes before the bell. She touched his face—gentle hands hardened by years of picking, washing, carrying. “I’m going to find the way,” she whispered. “To the river. To Freedom Road. I just need to see how they cross.”

Marcus, older and more cautious, warned her not to rush. But Sarah was tired of waiting. Tired of knowing the window for escape always closed faster than it opened.

“Promise you’ll wait for me,” she said.

He promised.

Neither knew this would be the last real conversation they would ever have.

That afternoon, near the riverbank where the water widened into mirror-like stillness, Sarah was discovered. Accounts differ on whether she was spotted first by dogs or by men, but all agree the patrol caught her before sunrise had fully broken. She was brought back on foot—not with ceremony but with noise. The men who apprehended her jeered and joked, their laughter carrying through the trees long before they reached Thornwood’s yard.

She was not the first enslaved person to be dragged home from the river. But she would be the last whose punishment set off a chain reaction that would come to be known, decades later, as The Thornwood Reckoning.

The Whipping Post Under the Magnolia Tree

The punishment was announced in the same tone a planter might use to order tea. Twenty lashes. A public example. “To prevent further foolishness.”

Christopher Hail, master of Thornwood Plantation, was known for maintaining a veneer of civility that often made his decisions more chilling. He spoke softly, smiled easily, and had a reputation for “fairness” that evaporated the moment someone attempted escape. Hail’s calm demeanor, preserved in photographs and family letters, never hinted at the ruthlessness beneath.

The enslaved people were pulled from their tasks and forced into a circle in the yard. Marcus stood in that circle. His chest rose and fell with the kind of breath that comes before panic or explosion. He did not move. He did not speak. The rifle pressed into his ribs ensured he wouldn’t.

Witnesses later described the moment Sarah was tied to the post: the metallic click of locks closing over her wrists, the tear in her dress, the look she cast over her shoulder. It was the look that haunted Marcus most. Not fear. Not regret. Just love—and something else, something heavier.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered to him.

The details of the punishment that followed have been preserved in oral histories but need not be repeated here. Suffice to say it was prolonged, excessive, and intended not simply to discipline one woman but to terrorize an entire community. Those who watched remembered the sound. The way the air changed. The way time stretched.

It ended only when her body finally went limp.

The overseer walked away laughing.

Marcus carried her to their cabin himself.

The Death That Became a Catalyst

For hours after the yard emptied, Marcus tried to save her. He used water from the well, herbs taught to him by family long since sold away, whispered prayers he hadn’t spoken since childhood. But Sarah’s breathing grew shallow, then strained, then disappeared entirely.

When Marcus realized she would never wake again, the scream that tore through the cabin was loud enough for some field hands to hear. Some said birds shot up from the cypress trees. Others said the sound reached the swamp basin itself.

Something in him broke. Something else hardened.

By dawn, Marcus had vanished. The cabin contained only Sarah’s body—laid gently, respectfully, as though he’d performed the last rites of someone who had never been allowed to live freely.

No one bothered looking for him.

The plantation assumed he had run north.

They were wrong.

He was not running.

He was becoming.

Blackwater: A Landscape That Did Not Forgive

To the enslaved, Blackwater was more than a swamp. It was a place of spirits—of those who had refused chains even in death. Older men told stories of people who walked into its depths and never came back. Women whispered that the fog carried messages for those willing to listen. Children were taught never to go near it. Not even the bravest hunters entered without fear.

The swamp was said to swallow men whole.

That was exactly why Marcus went there.

In the days that followed, he moved without intention or awareness, his mind trapped in the moment Sarah slipped away. Hunger did not register. Heat did not deter him. The reeds cut his legs, thorns pulled at his clothes, but he walked deeper still, a ghost seeking its own burial.

It was only when the ground beneath him turned suddenly soft—when the mud began to pull him downward—that instinct resurfaced. He grabbed a cypress root, fought the pull, and dragged his body onto solid land.

That moment, he would later tell no one, was the instant he understood two things:

He did not want to die.

He could not go back.

A man who loses everything often sees the world clearly for the first time. Marcus looked into the swamp’s dark mirror and saw not grief, but purpose.

The men who killed Sarah lived confidently behind rifles, dogs, and the arrogance of power.

The swamp offered something different.

A place no white man understood.

A place where their strength meant nothing.

A place where justice—real justice—might finally exist.

The Making of a Phantom

Marcus did not simply hide in Blackwater. He adapted to it. Days passed, then weeks. He learned which parts of the swamp were sound and which were traps. Which branches bent and which snapped. Which shadows were trees and which were eyes watching him back.

He found a dry island—a raised patch of land hidden beneath layers of moss and mist, invisible to anyone who didn’t already know it was there. He built a shelter so low and camouflaged that a man could walk past and never notice. There, he ate what the swamp gave him. Roots. Birds. Fish speared at dusk.

But survival was not his purpose.

He watched the plantation.

He learned the patrol routes, the jokes the men made, the habits they took for granted.

The slave catchers who dragged Sarah back—men who treated cruelty as entertainment—began entering the swamp again, searching for runaways.

Marcus followed them. He memorized each gesture, each shortcut, each careless assumption that Blackwater was nothing more than another patch of wilderness waiting to be conquered.

He knew something they did not:

The swamp noticed everything.

And it would obey the hand that understood it.

Fear Begins With One Missing Man

When Daniel Foster disappeared, people assumed he had been swallowed by one of Blackwater’s bottomless sinks. It had happened before. No one questioned it. No one searched long.

But Hayes, the leader of the patrol, returned pale and shaking. He had seen something carved into a tree near the place Foster vanished.

A single name.

Sarah.

He did not know who she was. He did not need to.

Someone did.

Someone alive.

Someone watching.

Two weeks later, Thomas Webb vanished. This time, there was no ambiguity. He did not simply fall, nor was he taken by an animal. The scene that awaited the militia patrol was deliberate. Measured. Purposeful. “It was as if the swamp itself delivered a message,” one descendant recalled.

And again, nearby, another carving.

Not a name.

A sentence.

“She felt worse.”

The words spread through the region like a fever. The enslaved whispered them with something approaching reverence. The planters whispered them with something approaching fear.

A pattern was forming. And it pointed not to a band of runaways, nor to a wild animal, but to a single man moving through water like a shadow, a man who knew every tree root and every whisper of fog.

Marcus had become a rumor.

A warning.

A presence.

And soon, he would become something far more unsettling.

What Died With Sarah

When a woman dies under a system of absolute power, the world around her expects silence. The slaveholders expected mourning to be contained. The enslaved expected the pain to be swallowed. The structure of the plantation depended on it.

But this time, the silence did not mean surrender.

It meant recalibration.

The death of Sarah Thorn was not the tragic end of an enslaved woman’s attempt to escape. It was the beginning of a reordering the white men of Thornwood could neither predict nor comprehend.

Because Marcus had made a promise.

And the South had forgotten that promises made by people with nothing left to lose are the ones most likely to be fulfilled.

PART II — The Swamp That Learned His Name

By late July 1862, the mood on Thornwood Plantation had shifted. The men who once strutted across the yard with rifles on their shoulders now moved with the uneasy vigilance of people realizing the rules had subtly changed. First Foster vanished. Then Webb. Two men gone, without trace or body, swallowed by the same swamp they believed could swallow only the enslaved.

But the enslaved community knew better.

“It wasn’t the swamp,” said Delilah Freeman, whose great-great-grandmother lived on Thornwood during the summer of 1862. “People whispered another story—one they never said outside the cabins. They said Marcus came back.”

No one saw him return. No one needed to. The evidence appeared in ways the plantation had no language to interpret—deeper footprints than any animal, carved messages that read like accusations from the dead, and above all, fear. Fear that arrived slowly at first, then all at once.

The planter’s world depended on the belief that violence traveled only one direction: downward. But in the humid dark of Blackwater, something was rising.

And it was watching.

The Anatomy of Vanishing

Historians examining the Thornwood disappearance records note something striking: the speed with which panic set in. Two patrolmen missing in a span of twelve days was not normal. Even in the most treacherous wetlands, experienced hunters didn’t simply vanish without leaving a rifle, a hat, a single torn scrap of clothing.

Except Foster had left something:

A tree, carved with a name no white man remembered—

SARAH.

The second disappearance, however, left far more than absence.

It left intention.

Thomas Webb’s corpse, when finally discovered by a search crew from the neighboring Lawson Plantation, revealed a pattern of shallow cuts—hundreds of them. The coroner’s ledger entry, preserved in the East Parish Courthouse, reads:

“Lacerations superficial, deliberate. Death by exsanguination likely preceded by prolonged torture.”

But it is the final line of the entry that stands out:

“No evidence of animal interference.”

Which, in a swamp teeming with alligators, raccoons, buzzards, and feral hogs, is telling.

Whoever did this wasn’t an animal.

He was leaving messages.

How a Ghost Is Built

To understand how one man could haunt thousand-acre wetlands, you must understand Blackwater itself. The Achafalaya Basin—called Blackwater locally in the 1800s—was not merely dangerous. It was alive in a way the plantation world was not prepared for.

It was a place where white men only visited with rifles, but where Black men—hunters, fishermen, fugitives—learned to read nature like a language.

Marcus had grown up in it.

He knew which mud was solid, which mud was quick, which water reflected harmlessly and which hid sinkholes forty feet deep. He knew that the threshold between land and swamp is not a line but a negotiation. And after Sarah’s death, he learned something else:

The swamp could be shaped.

Marcus dug pits and disguised them with woven mats of branches and moss—a childhood skill refined into strategy. He carved thorn-laced branches into shallow water where a misstep meant infection. He scattered rattlesnake and cottonmouth nests near footpaths only he could navigate. He used rotted meat to draw alligators toward the routes patrols favored.

Most chillingly, he mapped which areas amplified sound—where a single snapped twig could echo like a rifle shot.

“People assume he hunted them,” says Professor Samuel Cross, a historian who has spent twenty years studying Louisiana maroon communities. “But if you look at the pattern, the truth is more unnerving: he made the swamp hunt for him.”

And the swamp obeyed.

The Patrol That Never Returned Whole

Hail, desperate to reassert control, summoned every hunter he could hire—twelve men hardened by war or wilderness. Some had fought in Mexico. Others had killed wolves for sport. All believed they could not be intimidated by a swamp or a runaway.

They entered Blackwater at dawn on August 3rd, moving in military formation.

They left in shambles.

Here is the reconstruction based on oral accounts, plantation diaries, and the testimony recorded three days later by Sheriff Abram Pike:

The pit opened first.

A veteran named Carson stepped on what looked like solid ground. The earth collapsed beneath him. He fell five feet into mud, impaling his legs on sharpened stakes.

The formation broke.

As the others worked to free Carson, they clustered—an error every wilderness fighter knows never to make.

The first spear struck.

A sharpened pole hurled from the tree line hit a man named Dutch in the shoulder. Dutch fell screaming. Eyes turned toward the left.

The second spear came from the right.

The third, from behind.

“Marcus wasn’t just attacking,” Professor Cross explains. “He was confusing direction. He made them believe multiple attackers surrounded them.”

Within minutes, the men panicked.

Six rifles fired wildly into fog thick enough to distort sound.

Someone shouted he saw a shadow in the trees.

Someone else insisted it was only vapor.

Then a shot rang out—friendly fire. A man named Ellison dropped.

“Nothing in that swamp killed Ellison,” wrote one of the survivors. “We killed him ourselves.”

Marcus appeared only once—according to reports from the two surviving hunters who didn’t later recant in fear.

They described seeing a silhouette emerge twenty feet away, covered head to toe in mud, eyes glowing with a steady, terrifying calm.

“He walked like he wasn’t afraid of anything,” the survivor wrote. “Like the swamp belonged to him now.”

Then he vanished into the fog.

The patrol retreated in full panic, carrying their wounded, abandoning fallen rifles. It was the only known armed retreat in Thornwood’s history.

Four men died. Eight returned. All swore they saw something that moved too quietly, too quickly, too deliberately to be human.

Hail, when he saw the survivors, reportedly whispered:

“Oh God. He’s after us.”

Pritchard’s Night of Reckoning

James Pritchard—the overseer who ordered salt rubbed into Sarah’s wounds—should have known he was living on borrowed time. He pretended he didn’t believe in ghosts. Yet he drank more each night. His lantern burned later. He slept with his pistol loaded on the table.

On the night Marcus came for him, Pritchard was drinking heavily in the big house after losing money to Hail in cards. He stumbled into his cabin and lit a lantern.

What happened next is preserved entirely through forensic reconstruction and the sworn testimony of two enslaved men who heard the noise.

Pritchard did not scream at first.

He dropped his glass.

He stepped backward.

He saw something in the corner darker than shadow.

Marcus crossed the cabin in two steps, muffling Pritchard’s mouth with one hand while the other closed around his throat. The overseer, drunk and soft, was no match.

Marcus dragged him across the yard in near silence.

To the whipping post.

The same post where Sarah had been tortured.

“He tied him up exactly the same way,” one witness recounted decades later. “Same chains. Same height. Same moonless sky.”

Marcus didn’t imitate cruelty.

He mirrored it.

Twenty lashes.

Counted aloud.

Measured.

Spaced.

Delivered with clinical precision.

For each lash Marcus spoke a number—low, steady, almost emotionless.

After the twentieth, Marcus opened a small bag.

Salt.

Witnesses claimed Pritchard screamed even through the gag. Some said that scream haunted the plantation for years.

Marcus left him alive—deliberately.

The guards found the overseer half-conscious, his back a ruin of blood and salt. But the message carved in the whipping post was what froze them:

FOR SARAH.

JUSTICE.

When the System Realized the Rules Had Changed

Within hours, Thornwood had turned from a proud plantation into a fortress.

Doors barred.

Guards posted.

Guns loaded.

Windows shuttered.

A reward quietly offered to neighboring counties.

But Marcus was no longer attacking patrols. He was now striking the heart.

And the next heart belonged to Christopher Hail.

Hail, the man who had ordered Sarah’s punishment, reportedly didn’t sleep for three nights. He kept men stationed at his bedroom door. He placed pistols under his pillow and at his bedside. He double-checked every lock.

But fear is a poor architect.

For all his precautions, Hail forgot one thing:

He had once hired Marcus to repair the chimneys.

The Night Marcus Stepped Out of the Hearth

Midnight. August 15th, 1862.

The fires in the big house had been extinguished due to the summer heat. The chimney bricks cooled in the night air.

That was all Marcus needed.

No one heard the scraping of bare feet against the interior brick. No one heard the soft thud when he dropped into the parlor. No one heard the quiet footsteps up the back staircase.

The guards stood outside Hail’s bedroom door, armed and alert.

Inside, the room was silent.

Minutes passed.

Then a crash.

Then a shout.

Then a scream.

By the time guards burst into the room, Marcus had already dragged Hail to the open second-floor window.

Hail begged.

Witness testimony differs—some say he promised freedom for the enslaved. Some say he promised money. Some say he prayed.

But all accounts agree Marcus said one thing before letting go:

“She begged too.”

Hail fell twenty feet. His body broke loudly on the flower bed. He survived—but his legs, hip, and back did not.

Marcus leapt after him, landed in the soil, and sprinted toward the swamp as bullets tore the night air.

He reached Blackwater.

No guard dared follow.

When Terror Gains a Name

What happened to Thornwood afterward wasn’t simply fear.

It was collapse.

Pritchard descended into madness, screaming about “the swamp demon” until he was institutionalized.

Hail sold the plantation at a loss and fled north to Philadelphia, where his family later documented his paranoia of dark corners and open windows.

Workers refused to enter Blackwater for years.

Rumors spread that on humid nights, you could hear someone sharpening a blade in the fog.

And in the oral histories of the enslaved—later freed, later ancestors—a new legend took shape:

The Man Who Made the South Feel Fear.

The Ghost of Blackwater.

The Husband Who Came Back.

But Marcus was not done yet.

Because the question remained:

If the men who caused Sarah’s death had been punished…

…what was left for the man who had lived through it?

PART III — The Ghost Who Refused to Die

In the months following the attack on Christopher Hail’s plantation, the entire region around Thornwood shifted into a strange, uneasy calm. The whip cracked less often. Patrols moved in groups of four instead of two. Men who once strode across the property with an air of invincible dominance now walked with their eyes lowered and rifles held close, glancing at shadows as though they had suddenly realized the world held more of them than sunlight.

For the first time in their lives, plantation men were afraid of the dark.

The enslaved community, however, behaved differently. Quietly, without celebration, they began to speak of Marcus in a new way—not as a runaway or a man broken by grief, but as a figure who existed somewhere between man, storm, and judgment.

“He wasn’t a murderer,” said archivist Naomi Givens, whose ancestors lived on Thornwood. “He was something else. He was the consequence.”

The South had long operated under the belief that enslaved people were subjects without agency, without power, without the ability to retaliate. But in the summer and autumn of 1862, that fantasy cracked. A man had shattered the hierarchy. A system built on fear suddenly discovered it could feel fear back.

And the fear had a name whispered in every cabin and corridor:

Marcus.

Sarah’s husband.

The Ghost in the Swamp.

But legends rarely stay still.

In the weeks after Hail’s fall, Marcus’s story entered its final phase—his disappearance, his transformation, and the legacy that outlived him.

The Week the Overseers Refused to Enter Blackwater

Christopher Hail did not die after being thrown from his second-floor bedroom window. Instead, he lived in agony. His legs were broken in multiple places, his hip shattered, his lower back crushed. Doctors who visited him during the following weeks documented a level of pain so intense that one wrote:

“He wakes in the night screaming that the man is coming back. We cannot convince him otherwise.”

Hail refused to stay alone. He demanded constant guard rotations, insisted the shutters remain bolted, and banned his household staff from opening the windows even in the oppressive heat. He slept with two pistols and a hunting rifle within arm’s reach.

And still—according to testimonies collected decades later—he startled at every creak of wood, every wind-dragged branch scraping the house, every shift in the shadows.

The overseers, meanwhile, were shaken to the core by what had happened to Pritchard. The physical wounds he endured healed in a grotesque lattice of scar tissue—but the psychological wounds never closed. He stopped walking near the whipping post entirely, choosing instead to take long, roundabout routes to avoid being in its line of sight. He drank constantly. He muttered to himself about “eyes in the swamp.”

He never again entered Blackwater.

Neither did any overseer.

“It was a turning point,” says Professor Cross. “For maybe the first time in Thornwood’s history, white men refused to go where enslaved men once fled.”

That reversal alone was enough to destabilize the plantation’s operations. Without the ability to send armed men after runaways, Thornwood became vulnerable. More enslaved people fled. More succeeded.

Marcus had not only avenged Sarah.

He had broken an entire system’s confidence.

The Disappearance of Marcus: A Vanishing That Became a Myth

The most puzzling element of this story comes after the night Hail fell. Marcus escaped into the swamp, disappearing into the fog with the same silence that defined all of his movements.

He was not seen the next day.

Or the next week.

Or ever again.

Dozens of accounts emerged over the years, none provable, some contradictory, many wrapped in folklore:

A fisherman claimed he saw a tall figure slip across the waterline at dawn, moving like a shadow between trees.

A Confederate deserter swore he saw a man watching Union troops approach New Orleans in 1862.

A freedman in 1865 told federal officials he met a quiet hunter in the hills near Natchez who carried a scar on his cheek and never gave his name.

None of these sightings were confirmed.

“His disappearance is the part that elevates him from man to myth,” says Dr. Ellen Ruiz, a historian of maroon communities. “There is no body. No grave. No record. Only consequences.”

There are three primary theories regarding Marcus’s fate:

THEORY 1 — He Died in the Swamp

Many historians believe the simplest explanation: that Marcus succumbed to infection, exhaustion, or the swamp’s many silent dangers.

Blackwater had claimed countless lives over generations—runaways, hunters, poachers, even Confederate scouts. Bodies sank into its hidden sinkholes and never resurfaced.

“It’s entirely plausible he died within days,” says Ruiz. “But even if he did, the timing ensured his legend lived longer than his body ever could.”

THEORY 2 — Underground Freedom

Some believe Marcus followed the Union-controlled routes toward New Orleans.

By late 1862, New Orleans was under federal occupation. Thousands of enslaved people fled there. Union records list several men who match his approximate age and background but none conclusively identified him.

Still—this theory persists strongly among descendants.

“My grandfather always said he made it out,” said Gloria Bennett, a Thornwood descendant. “He said Marcus became a scout for the Union Army. He said freedom wasn’t a dream for him—he earned it.”

THEORY 3 — The Mountain Man

This theory, supported by a scattering of oral traditions across Mississippi and Alabama, claims Marcus survived the war and lived the rest of his life in solitary peace.

“Heard he lived in a cabin up in the hills,” one 1930s Works Progress Administration interview records.

“A big quiet man. Kind eyes. Didn’t talk about the past.”

These accounts all describe the same key features: tall, built like a tree trunk, soft-spoken, and carrying the weight of a man who had seen things no one else could understand.

No one knows if this man was Marcus.

But people believed it.

And sometimes belief is stronger than fact.

What Happened to Thornwood: The Collapse of a Plantation

After Hail’s injury, Thornwood Plantation declined rapidly. Its owner could no longer oversee daily operations. Pritchard, now erratic and unreliable, terrified even the enslaved people he once controlled.

Within a year:

Cotton yield fell by half

Several families escaped entirely

Overseers requested transfers to other counties

Rumors spread that the land itself was cursed

In 1863, with the Civil War tightening around the South, the plantation was put up for sale. Few buyers expressed interest—not due to soil quality or structural decline, but because of the story.

“You could not pay men to take that land,” says local historian Arty Simms. “Folks swore the swamp had taken a soul and wanted more.”

Hail sold Thornwood for pennies on the dollar to a distant cousin and left Louisiana entirely. He resettled in Philadelphia, where he lived the rest of his days an invalid, wracked by pain, unpredictable tremors, and night terrors.

He died in 1870 at the age of forty-seven, buried in a private cemetery with no mention on his tombstone of his years in Louisiana.

In the letters preserved by his descendants, one chilling line appears repeatedly:

“He is coming back.”

An Overseer in an Asylum

James Pritchard’s deterioration was even more dramatic.

After surviving the punishment Marcus mirrored upon him, Pritchard began to lose control of his mind. Witnesses said he woke screaming on most nights, certain he saw Marcus standing at the edge of his bed. He believed every shadow carried intention, every whisper carried meaning, and every storm was an omen.

In 1864, his cousin committed him to the East Parish Asylum.

The intake form reads only:

“Man suffers from delusions relating to the swamp, a figure in the dark, and a woman named Sarah.”

He died there ten years later.

His final recorded words:

“Tell him I’m sorry.”

Why Marcus Terrified the South More Than Any Rebellion

In the broader landscape of Southern resistance during slavery, Marcus’s story is unique. Most acts of retaliation were collective—revolts, uprisings, organized escapes. Marcus acted alone, moving like a phantom across terrain that enslavers assumed belonged to them.

But here is why his story mattered so deeply:

1. He used white men’s tools against them

Surveillance, trails, mapping, hunting, pursuit—skills plantation men believed only they mastered.

Marcus mastered them better.

2. He destroyed their certainty

White dominance relied not just on violence but on the belief that enslaved people could not resist.

Marcus shattered that illusion.

3. He operated where slavery had no language

The swamp was not a plantation.

It was not a ledger.

It was not a courtroom.

It was wild, ancient, indifferent—and Marcus became part of it.

4. He inflicted terror, the very tool slavery depended on

The same fear that kept enslaved people compliant now lived inside the overseers.

“They were governed by the same weapon they once wielded,” says Dr. Ruiz. “And they had no idea how to survive it.”

What the Story Means Today

The story of Marcus and Sarah has all the qualities of a Southern gothic myth—fog, vengeance, dark water, whispered warnings. But beneath the legend lies something more important:

A record of the emotional and moral collapse of a system that believed itself untouchable.

When the enslaved community spoke of Marcus afterward, they did not describe a killer.

They described balance.

“Marcus gave people something slavery never allowed,” says Givens. “The idea that wrong could be answered. That suffering was seen. That one man could make plantation owners understand what pain really felt like.”

Today, Blackwater is still avoided by many locals. Hunters skirt its edges. Hikers keep their distance. The deeper swamps remain unmapped.

And on certain nights, when fog drapes the cypress knees like ghosts of the past, some claim they hear the distant scrape of a whetstone against steel.

Most dismiss it as frogs, crickets, or imagination.

Some don’t.

The Final Reckoning

In the end, this story is not about the violence committed against white men. Nor is it about the vengeance one man brought upon them. It is about the truth that the South spent centuries refusing to face:

Cruelty creates consequences.

Systems built on suffering eventually birth their own undoing.

And terror—true terror—is not supernatural. It is man-made.

Marcus did not haunt Louisiana because he wanted to.

He haunted it because the world had left him no other language.

His wife died trying to escape enslavement.

And the men who killed her lived their lives believing they would never answer for it.

They were wrong.

Sometimes justice does not come from courts, laws, or armies.

Sometimes justice walks out of the swamp with nothing left to lose.