Ezekiel the Legend: The Slave Who K!lled His Elderly Master, Married His Young Wife, Slave to Master | HO!!

Ezekiel the Legend: The Slave Who K!lled His Elderly Master, Married His Young Wife, Slave to Master | HO!!

No one was ever supposed to know what happened at Belmont Plantation in the spring of 1847. The records were sealed, the witnesses silenced, and the truth buried so deep that even mentioning his name became dangerous in parts of Louisiana.

But the truth has a way of leaking through time. It was found, decades later, in a water-stained courthouse ledger — a single line written in fading ink:

“Ezekiel, property of Master Fontineau, executed by his own hand the transformation that law and God alike forbade.”

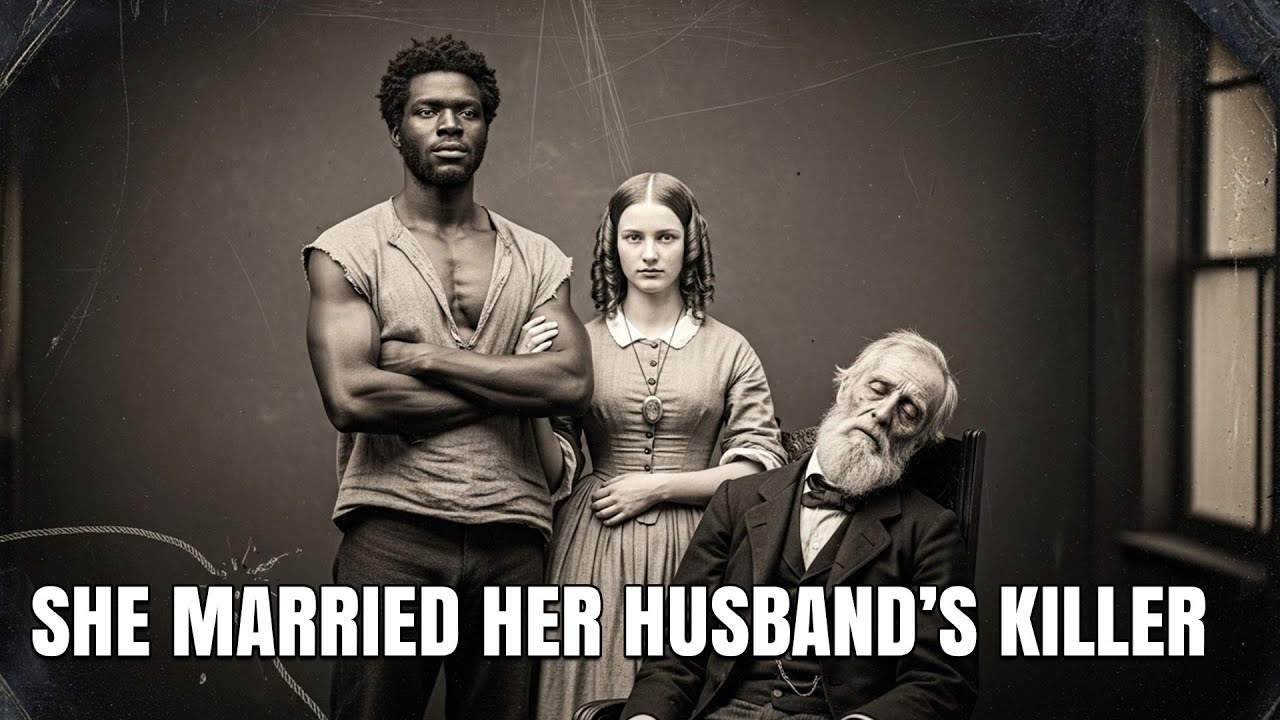

By the first winter of 1848, Ezekiel had done something that should have been impossible. He had gone from being property to being master. From the slave quarters to the master’s bed. From eating scraps in the kitchen to dining on fine china in the great house. And the woman serving him dinner was Clare Fontineau, the young widow of the man whose death had made it all possible.

The question that haunted Louisiana’s whispered histories was never whether he did it — but how many people had to die for such a transformation to occur.

The Master Who Was Dying

Belmont Plantation sprawled across three thousand acres of Mississippi Delta soil — land so black and rich it could grow fortunes. In the spring of 1847, Jean-Baptiste Fontineau, Belmont’s fifty-four-year-old master, was dying. Slowly. Painfully. Something was rotting him from the inside, a disease no doctor could name.

He was a cruel man, honest about his cruelty. He never pretended his slaves were family or spoke of Christian duty. “They are tools,” he once told a visitor. “And tools that don’t work get broken.”

But Fontineau’s real fear wasn’t death — it was irrelevance. He had no heirs, no legacy. So that February, he married Clare Deveau, a twenty-three-year-old from a ruined New Orleans family. She brought beauty and pedigree. He brought money and power.

To Clare, marriage to an aging planter was a kind of genteel imprisonment — gilded chains in place of iron ones. She didn’t yet know she’d entered a house already primed for revolution.

The Slave Who Watched Everything

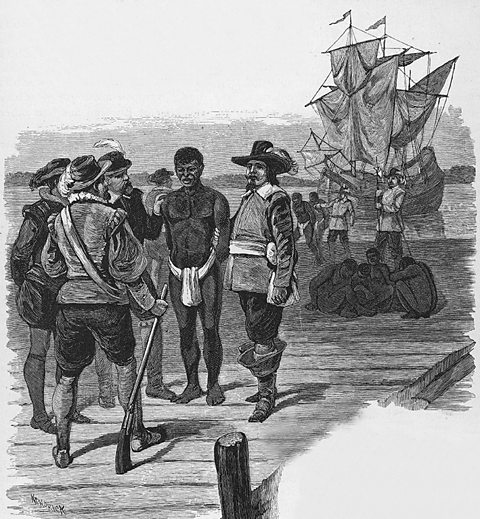

Ezekiel had been born on Belmont in 1817. His mother, Sarah, was a field worker who sang old river songs at night and died when he was eight. He grew up understanding the brutal mathematics of plantation life: people were numbers; life was currency.

But Ezekiel was brilliant — dangerously so. He taught himself to read by listening to the tutor of a white boy and tracing letters in the dirt at night. By fourteen, he could read better than most overseers. By twenty, he was keeping Belmont’s books.

Fontineau trusted him — admired his precision. Against the warnings of other planters, he made Ezekiel his personal attendant and later his business assistant.

What Fontineau never understood was that Ezekiel wasn’t just managing accounts. He was studying his master. Every weakness. Every fear. Every blind spot.

And when Clare Deveau arrived — young, frightened, and intelligent — Ezekiel saw in her not just pity, but possibility.

The Alliance of Necessity

By June 1847, Clare and Ezekiel were sharing secret glances that carried the weight of conspiracy. He showed her the plantation’s real books — the corruption, the violence, the theft. She saw the truth of her husband’s empire and began to question her place in it.

Their alliance began in whispers and ended in blood.

Fontineau’s health worsened. His skin turned gray, his memory faltered, his speech slurred. The doctors prescribed tonics and mercury treatments that only hastened his decline. None thought to examine the food and wine served daily by his attentive wife — food prepared by the one man Fontineau trusted completely: Ezekiel.

By autumn, Fontineau could barely sit upright. His will, drafted under “gentle encouragement,” left the entire plantation to Clare — and named Ezekiel executor and beneficiary.

Three weeks later, on October 26, 1847, Jean-Baptiste Fontineau was dead.

The coroner called it “failure of the organs.” The parish called it “God’s justice.” And in the quiet of the plantation house, Clare and Ezekiel called it something else entirely: freedom.

The Widow and the Freeman

The reading of the will sent shockwaves through Ascension Parish. Fontineau’s white relatives erupted — furious that a “negro servant” was granted freedom, authority, and ten thousand dollars. But the will was airtight. The lawyer, Theodore Barret, had witnessed it himself.

By the time challenges reached court, witnesses were missing. A doctor who’d tended to Fontineau died suddenly. A servant who might have testified was crushed in a “mill accident.” Within months, opposition dissolved into silence and fear.

In May 1848, Clare Fontineau and Ezekiel — now legally free — appeared before a distant parish judge and did something unprecedented. They married.

The parish reacted with horror. Neighbors severed all contact. Churches refused to recognize the union. But Clare and Ezekiel no longer needed society’s approval. They had Belmont.

And within Belmont’s gates, the world had turned upside down.

From Slave to Master

By summer 1848, Ezekiel was running the plantation. White overseers took orders from him. Merchants negotiated with him. He managed the accounts, set the quotas, controlled the labor.

A man who had once been whipped for reading was now signing contracts on embossed stationery.

But freedom built on slavery is a paradox that corrodes the soul. Ezekiel did not free the enslaved workers of Belmont. He told Clare — and himself — that it would be financial suicide, that he needed time to “stabilize.” In truth, he had become what he once despised: a man whose power depended on the bondage of others.

Some slaves saw him as a symbol of hope. Others called him a traitor. “He was one of us,” said a cook named Dina years later, “but when he gave orders, his eyes looked like the master’s.”

The Trail of Death

The transformation came at a staggering cost. Between 1847 and 1851, at least twelve people connected to Belmont died under suspicious circumstances.

Micah Holstead, the overseer who suspected too much — found in a swamp, his neck broken.

Dr. Raymond Quimo, who questioned Fontineau’s symptoms — dead of a “stroke.”

Marcus Fontineau, a cousin who threatened to reopen the case — found floating in the Mississippi.

A priest who hinted at hearing a damning confession — dead of fever weeks after being transferred.

And each time, the same quiet efficiency. No arrests. No witnesses. No evidence.

It was as if death itself worked for Belmont.

The Queen in the Gilded Cage

Clare’s private journals, discovered a century later, reveal the psychological toll. Her initial passion had curdled into dread. “I am afraid of my husband,” she wrote in 1849. “Not that he will harm me, but of what he has become.”

She understood she was complicit — bound to Ezekiel by shared guilt. “We are prisoners,” she wrote, “chained together by blood.”

Ezekiel, meanwhile, grew increasingly paranoid. Betrayal had become second nature. He trusted no one. He began to sense that even Clare — his co-conspirator, his accomplice — was a liability.

Freedom had made him untouchable. Power had made him alone.

The Collapse of the Empire

By 1851, the myth of Ezekiel had consumed the man. The parish elite, terrified of his precedent — a Black man wielding authority over white labor — plotted to remove him. Each plot ended in fire, accident, or suicide.

But inside Belmont, revolt was brewing. A slave named Isaiah, who had once worked beside Ezekiel in the fields, led a failed rebellion. He was sold “down the river.”

That same year, Ezekiel began freeing people — not out of altruism, but exhaustion. “I am tired of fear,” he told Clare. “Tired of what I have become.”

By 1854, Clare was dead of tuberculosis. Belmont was abandoned. And Ezekiel disappeared.

The Legend and the Confession

He was seen years later in Mexico — a wealthy man of color who never spoke of Louisiana. Letters found in 1890 confirm what history long suspected: Ezekiel murdered his master, the overseer, the priest, the doctor, and every rival who threatened him.

“I murdered at least twelve people,” he wrote. “Each death brought me closer to freedom — and further from my soul.”

He called himself “a monster born of monstrosity,” a man forged by a system that offered no moral path to salvation.

The Lesson That Survives

In 2003, archaeologists excavating the Belmont site found a hidden chamber beneath what had been the master’s study. Inside lay ledgers, journals — and a rifle, the same one that had killed Jean-Baptiste Fontineau. Carved into its stock were three words:

“Remember the cost.”

That’s all Ezekiel left behind — not a legacy, but a warning.

His story resists neat judgment. He was both victim and villain, hero and horror — a man forced to choose between submission and damnation, and who discovered that sometimes they are the same.

History buried him because he didn’t fit the myth of slavery as simple cruelty or simple nobility. He proved that oppression can corrupt not just the powerful, but the powerless too — that in a world without moral choices, even freedom can be a tragedy.

“Liberation achieved through evil methods,” Ezekiel wrote near the end of his life, “is not liberation. It is another form of captivity.”

He escaped his chains, only to be enslaved by guilt.

And in that paradox lies the terrible brilliance of his legend — the slave who became the master, the man who proved that power and freedom are never the same thing.

Remember the cost.